- About

- Intara

- Capabilities

- Advisory

- Resources

- News

- Store

Janes - News page

- Home

- News

Firm intentions: China's corporate acquisition strategy

18 July 2022

Chinese acquisitions of foreign firms that develop strategic technologies are on the decline, Janes data shows. Despite this, Beijing's strategy to support military gains through corporate takeovers remains a key part of its modernisation programme, Jon Grevatt reports

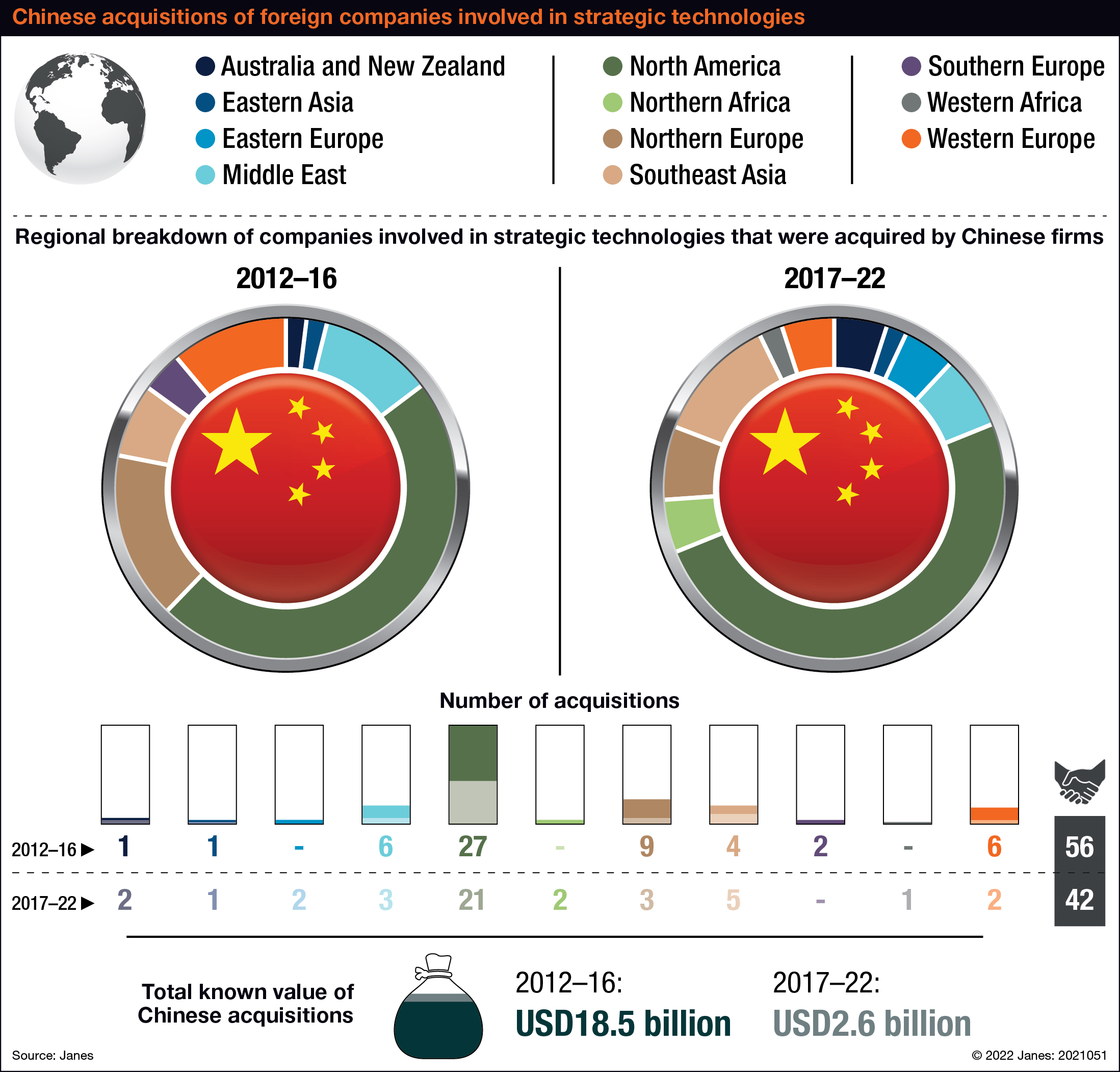

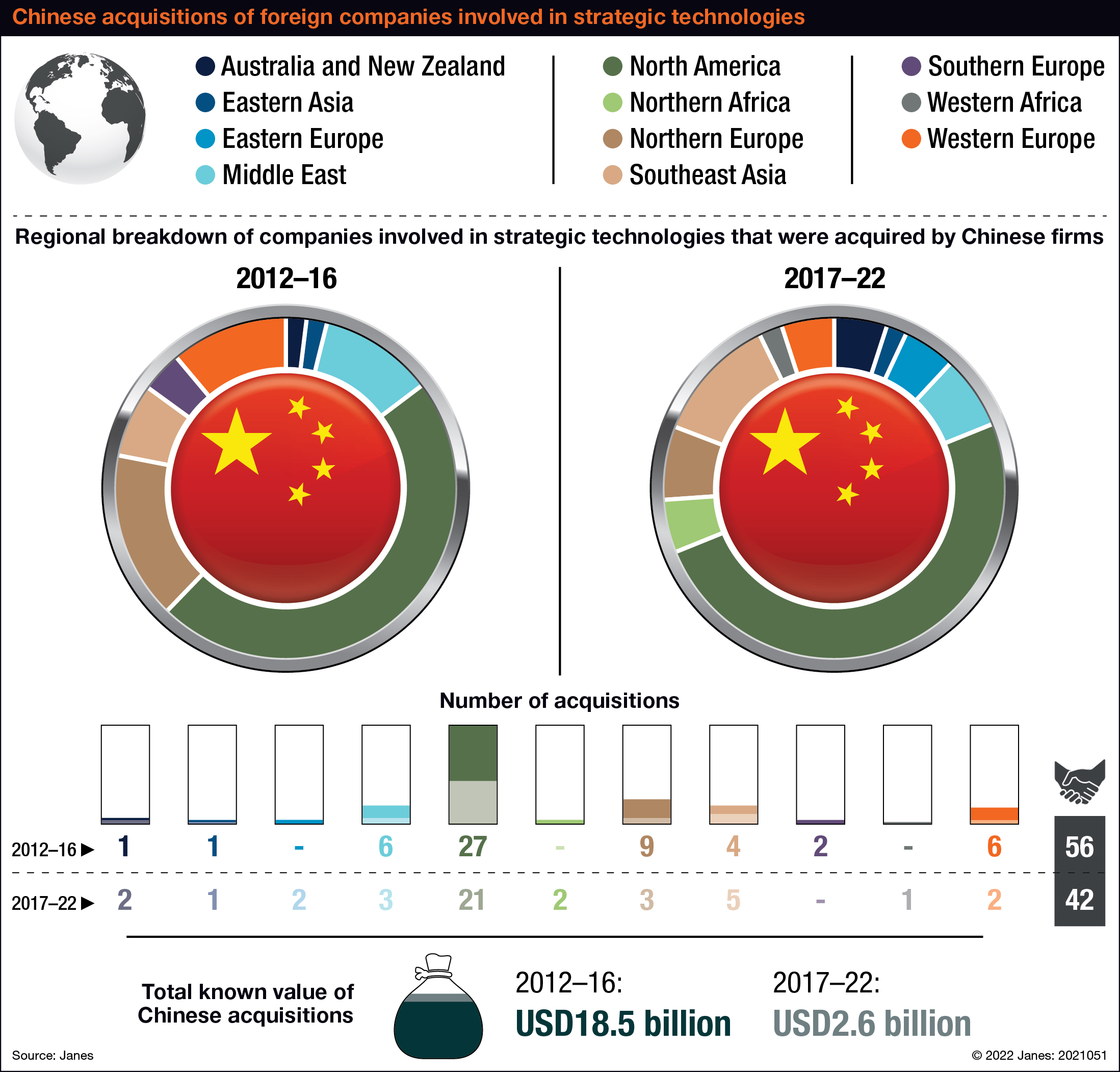

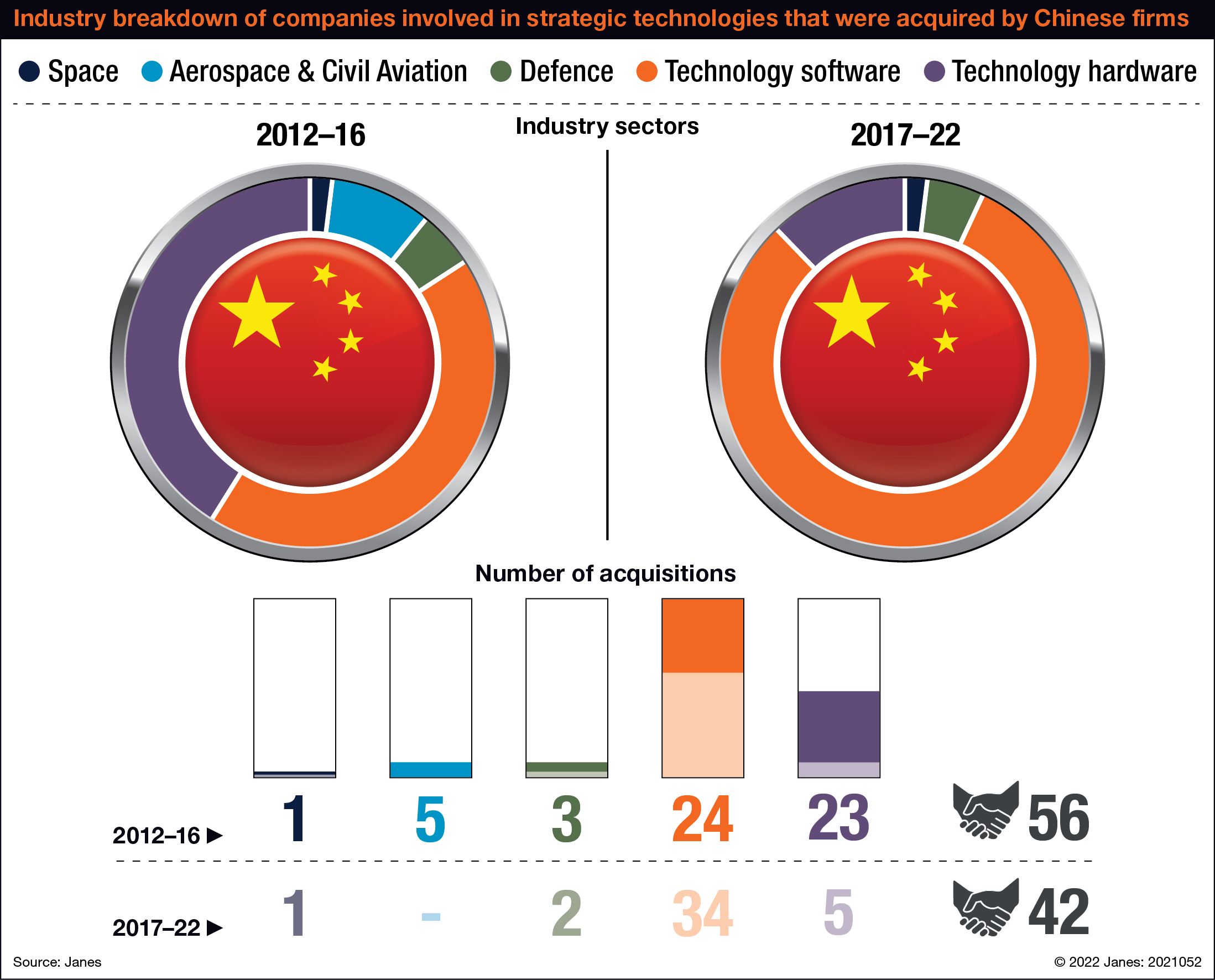

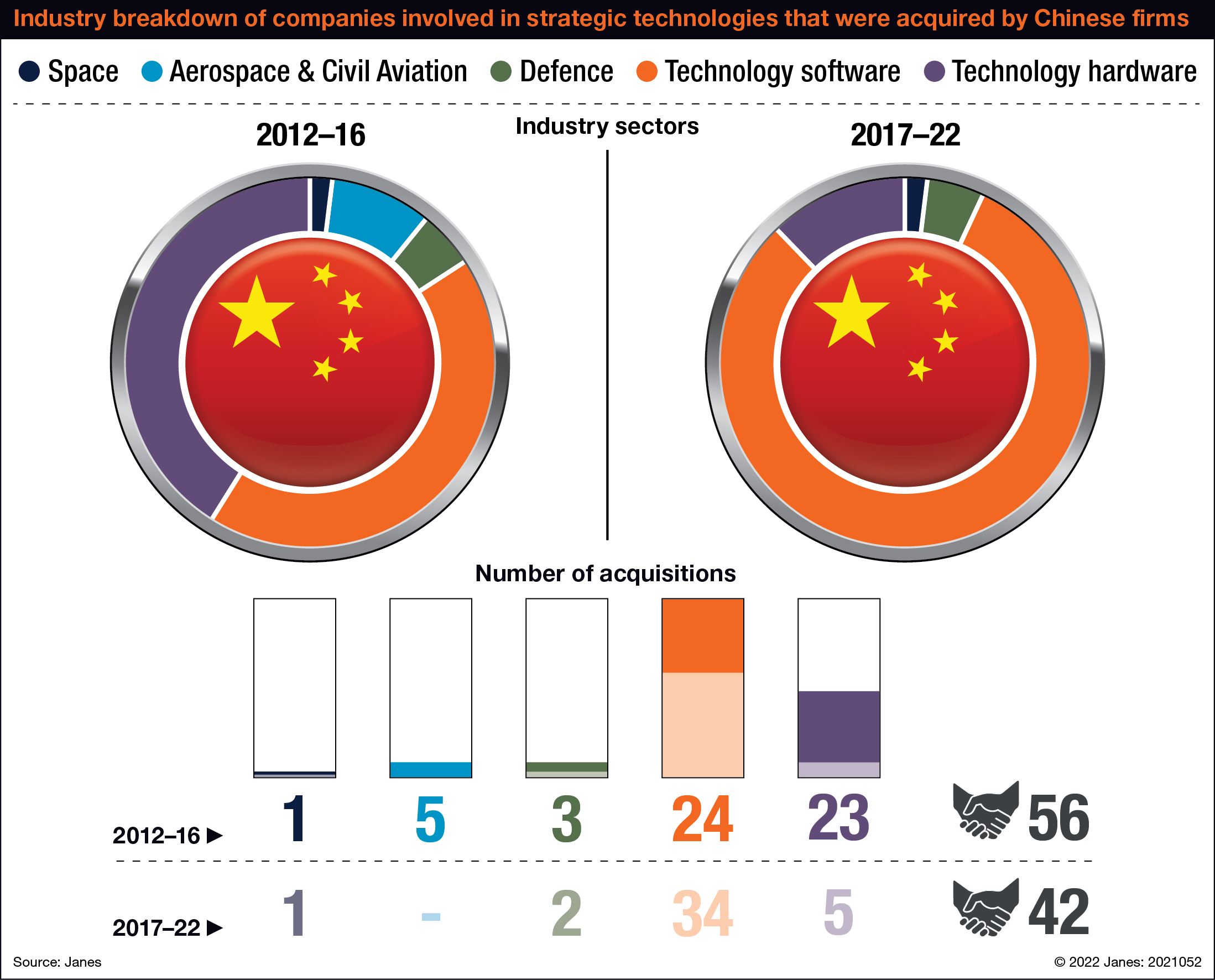

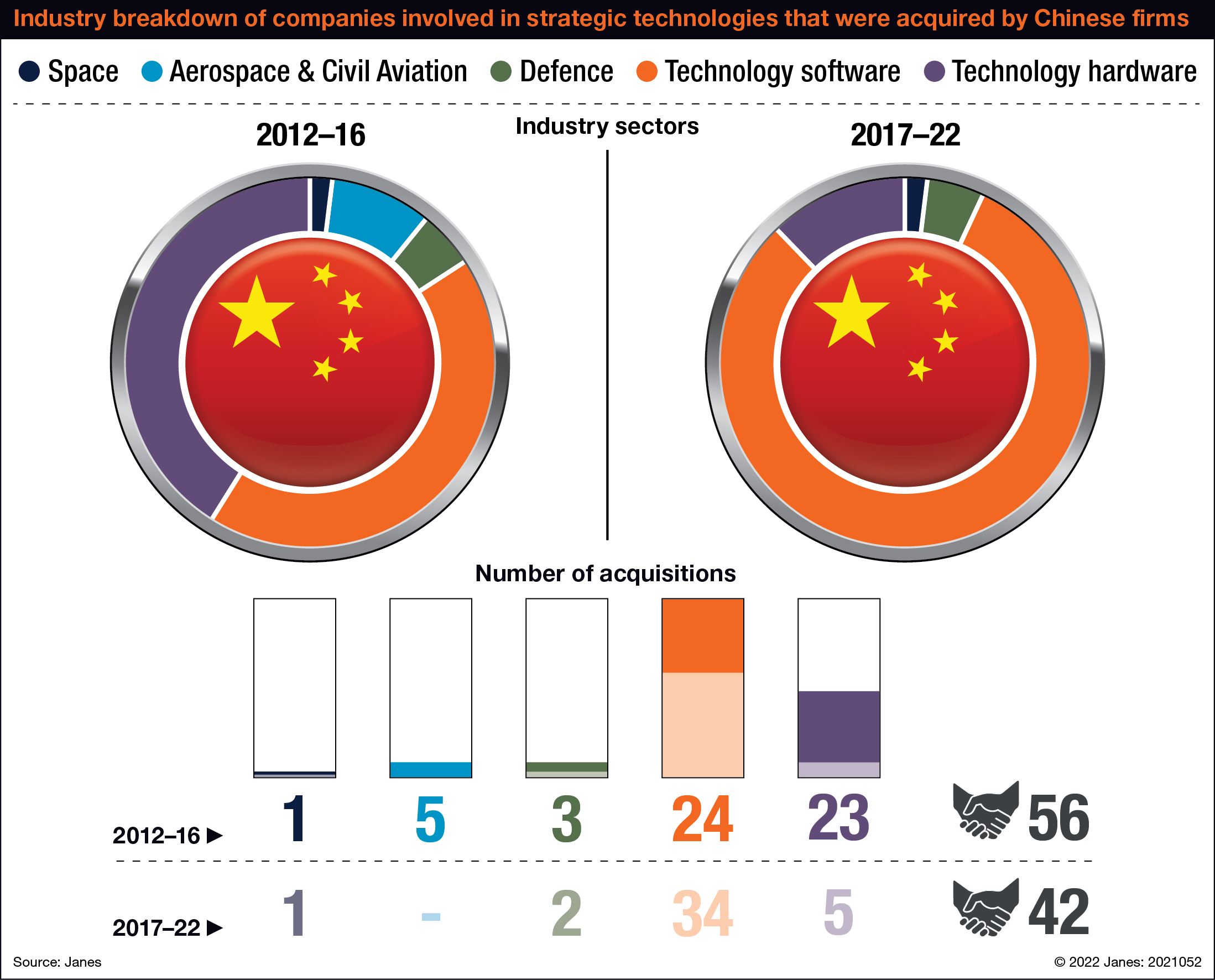

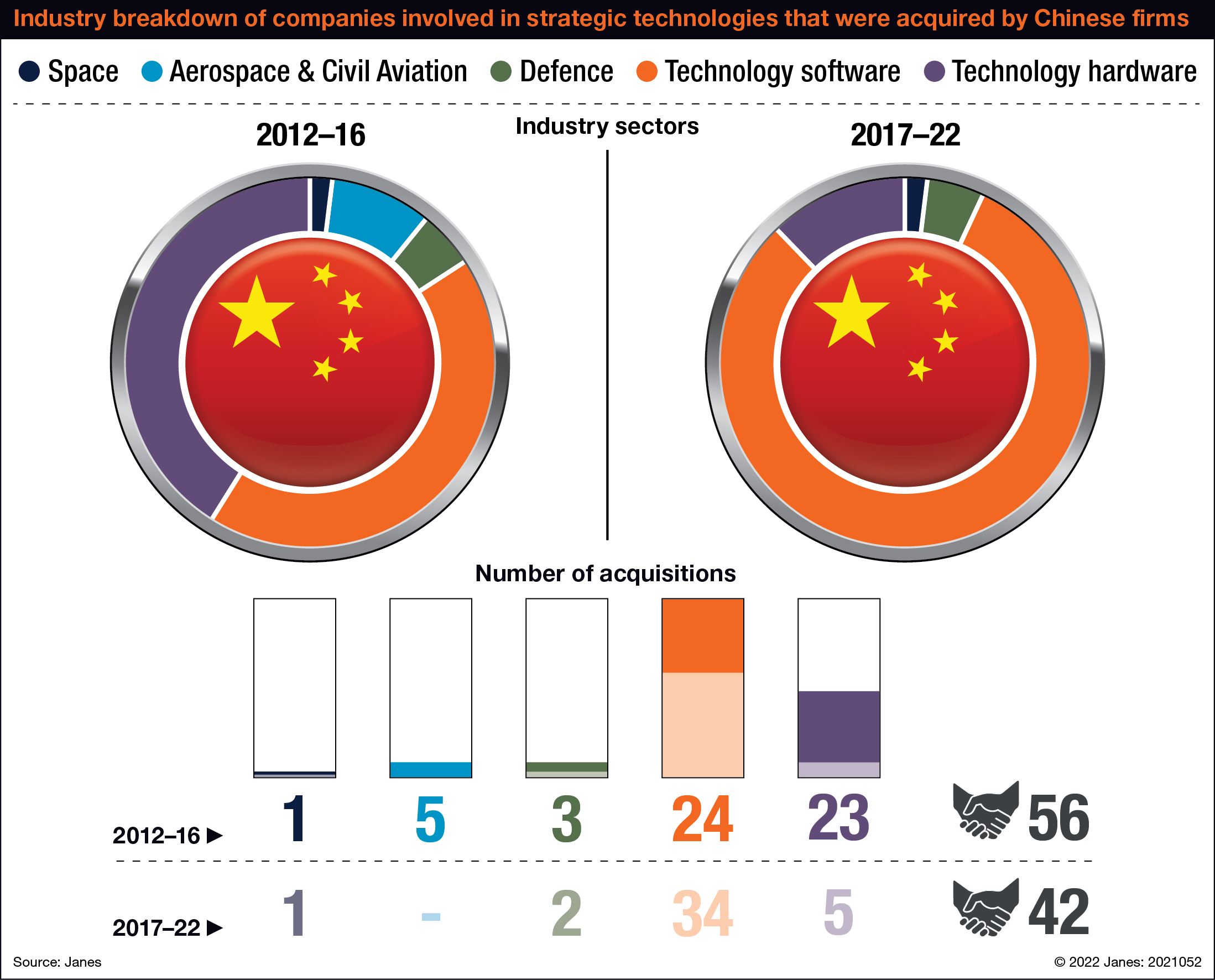

China's acquisitions of foreign firms that develop technologies that could benefit the People's Liberation Army (PLA) have declined in recent years, Janes IntelTrak data shows.

The decline is likely linked to increased international scrutiny of Chinese investment in local firms involved in these strategic sectors, which include aerospace, semiconductors, sensors, communications, navigation, robotics, and artificial intelligence (AI).

Despite this, Janes data also suggests that such corporate takeovers are likely to remain a crucial method for China in gaining access to foreign technologies in line with its increased emphasis on military-civil fusion (MCF).

During 2017–22 the number had declined by 25% to 42 foreign acquisitions. Again, most of these target firms were located in the US and involved in sectors such as visual recognition, AI, unmanned systems, Internet of things (IoT) technologies, semiconductors, navigation, and cartography.

In part, the difference between the two periods can be linked to variations in Chinese and foreign economies, which prompt firms periodically to either tighten their belts or look to secure inward investment.

However, it is the effort by foreign governments – including those in Australia, India, Japan, the US, and the United Kingdom – to ensure greater protection against investment from China in strategic technologies that is likely to have had the biggest impact on the Chinese acquisition strategy.

Many of these investment measures have been introduced since the start of Covid-19, with the goal to protect technology companies destabilised by the economic impact of the pandemic.

However, while concerns about Covid-19 are easing in many countries, it appears unlikely that such rules will be reverted given concerns held by many governments about China's strategic motives.

Such measures mean that China's private and state-owned companies face high barriers in their efforts to invest in or acquire foreign technology firms – especially those in the West – that are looking for such investment.

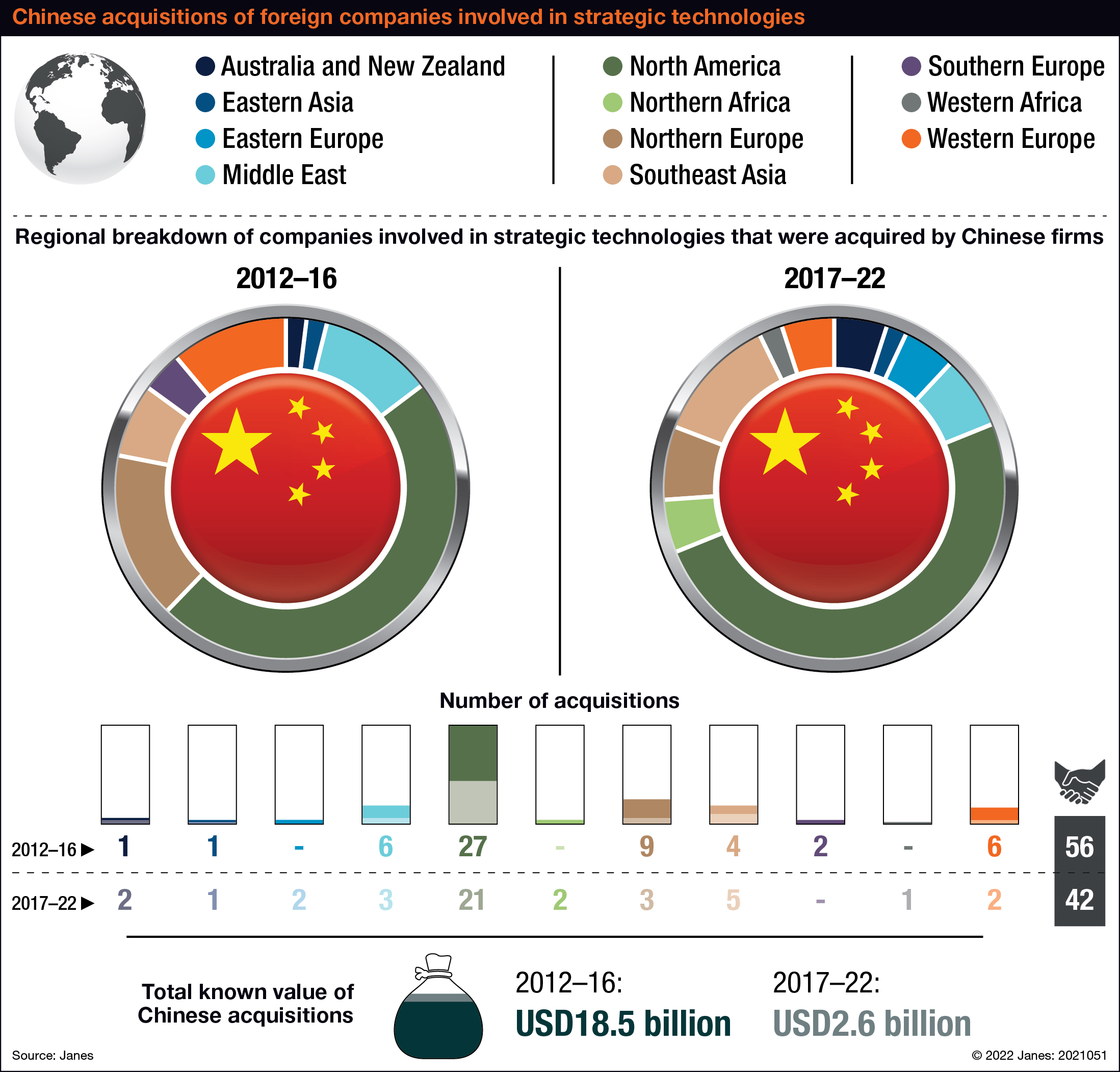

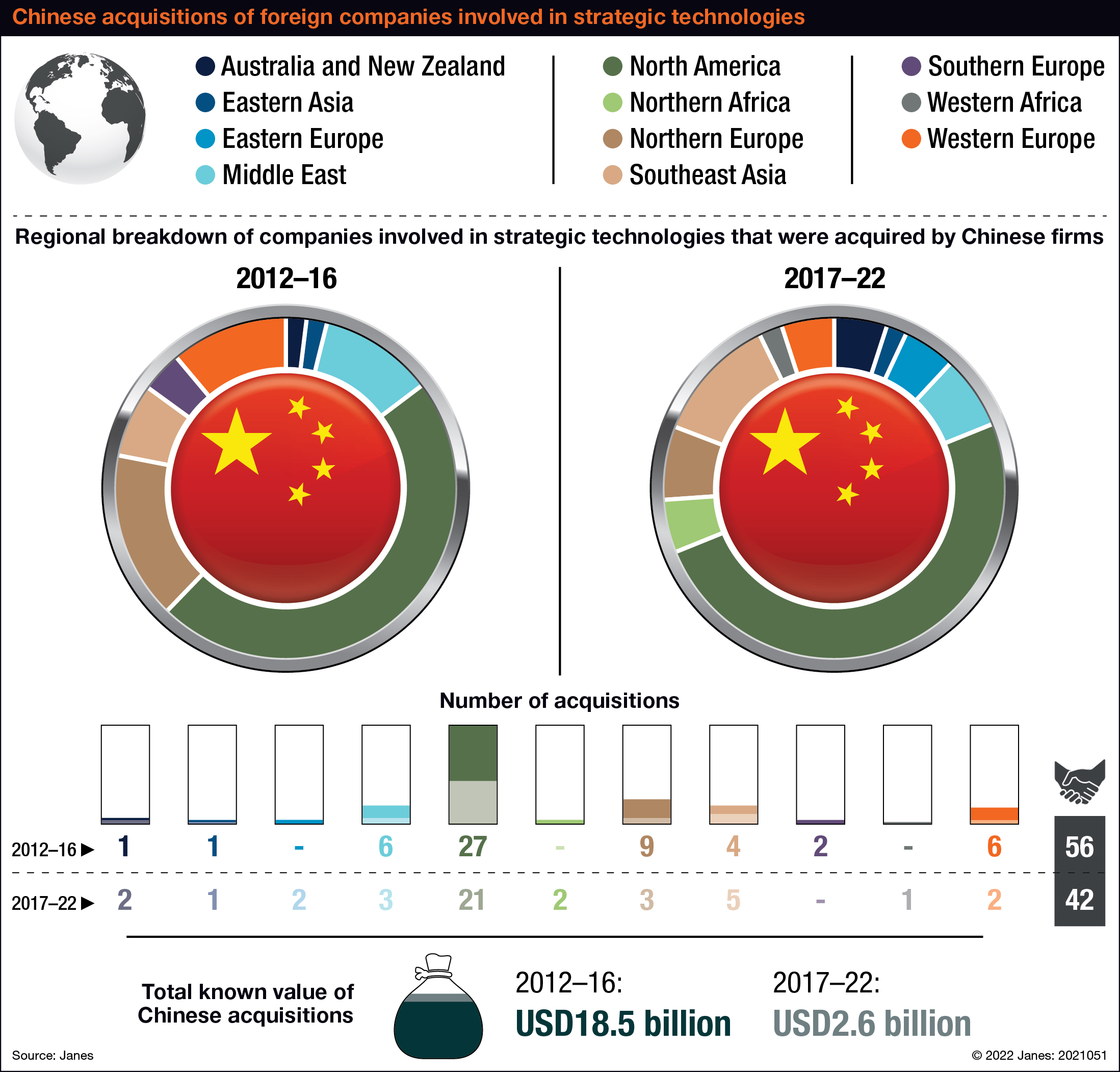

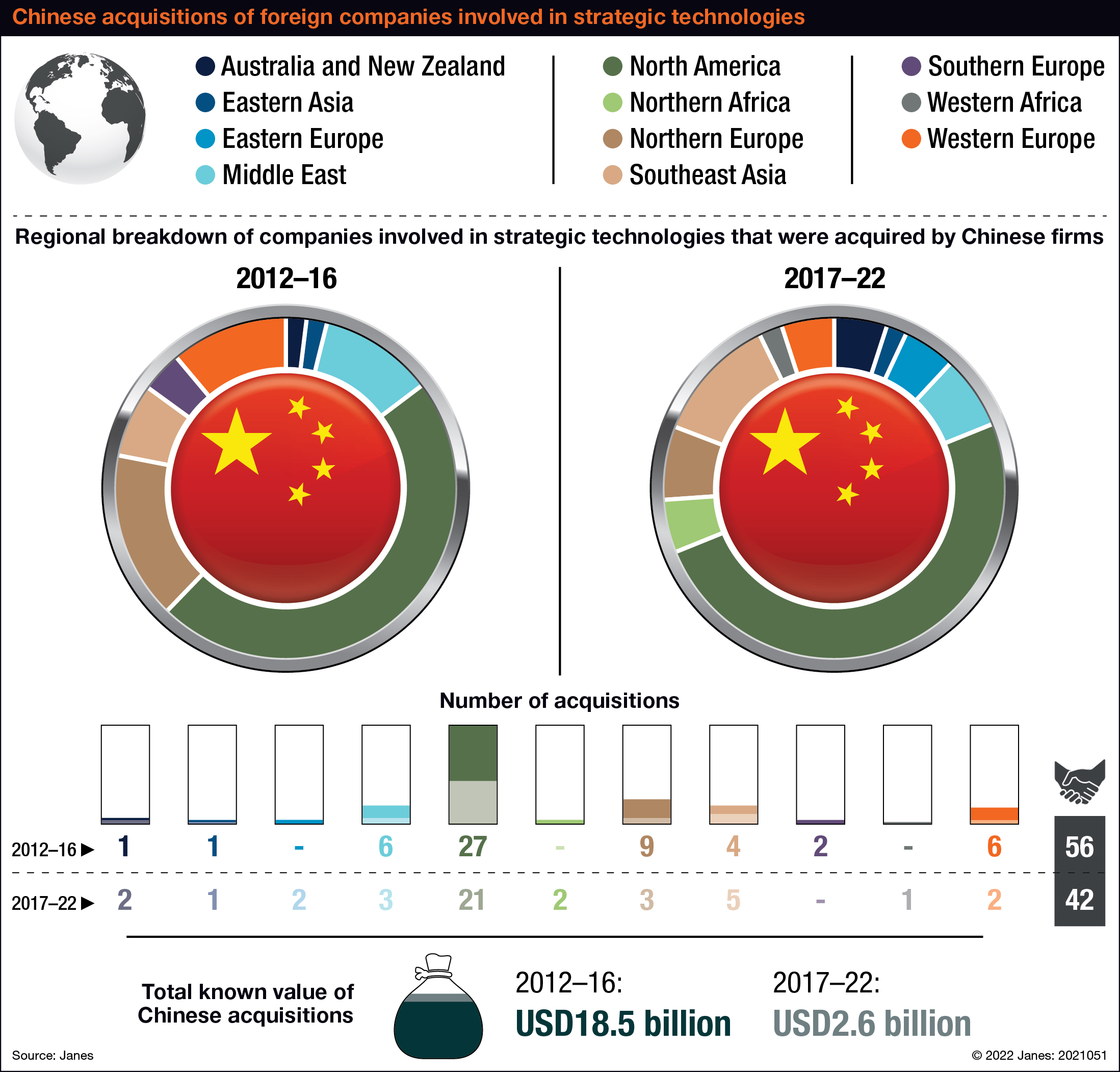

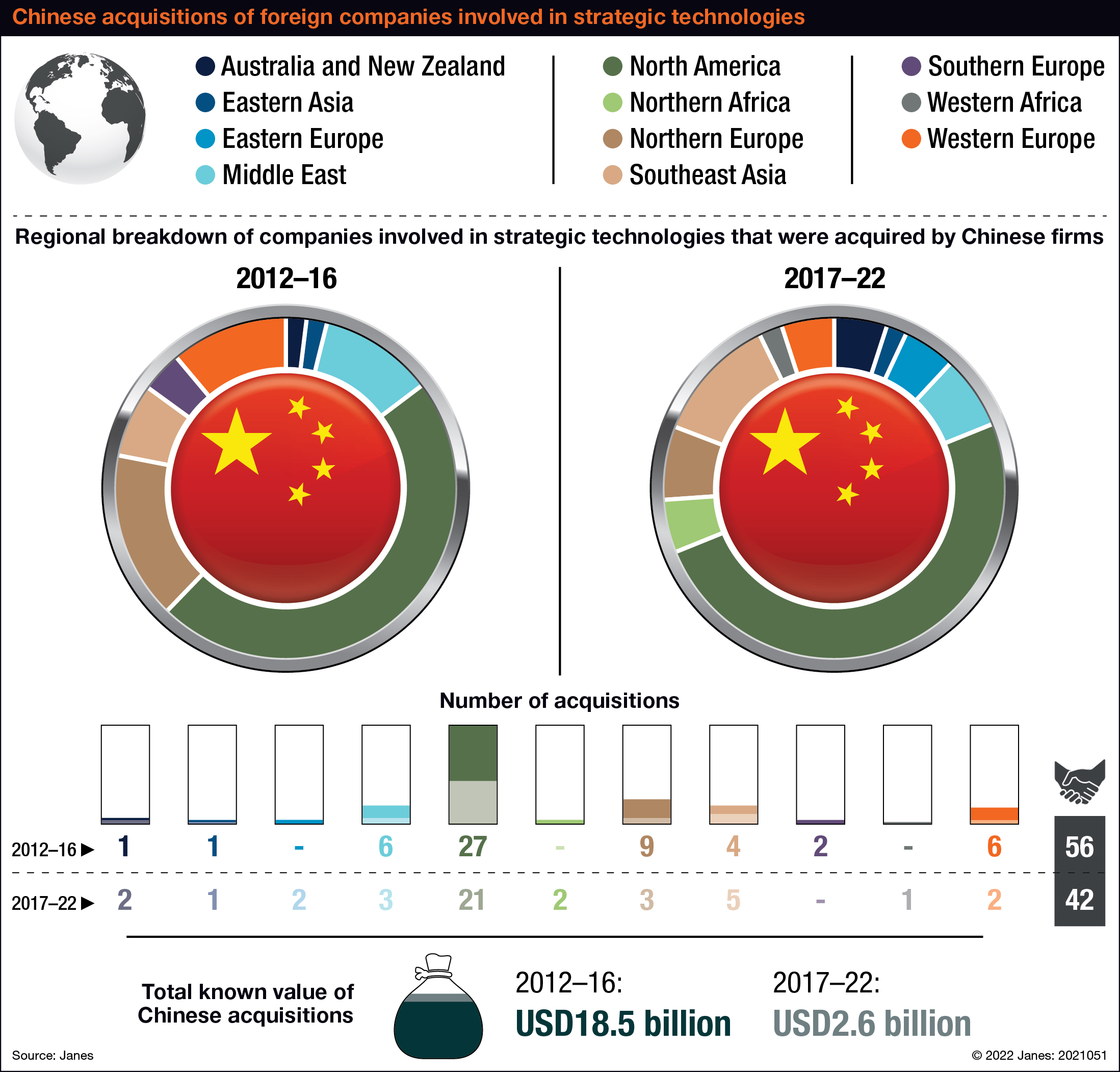

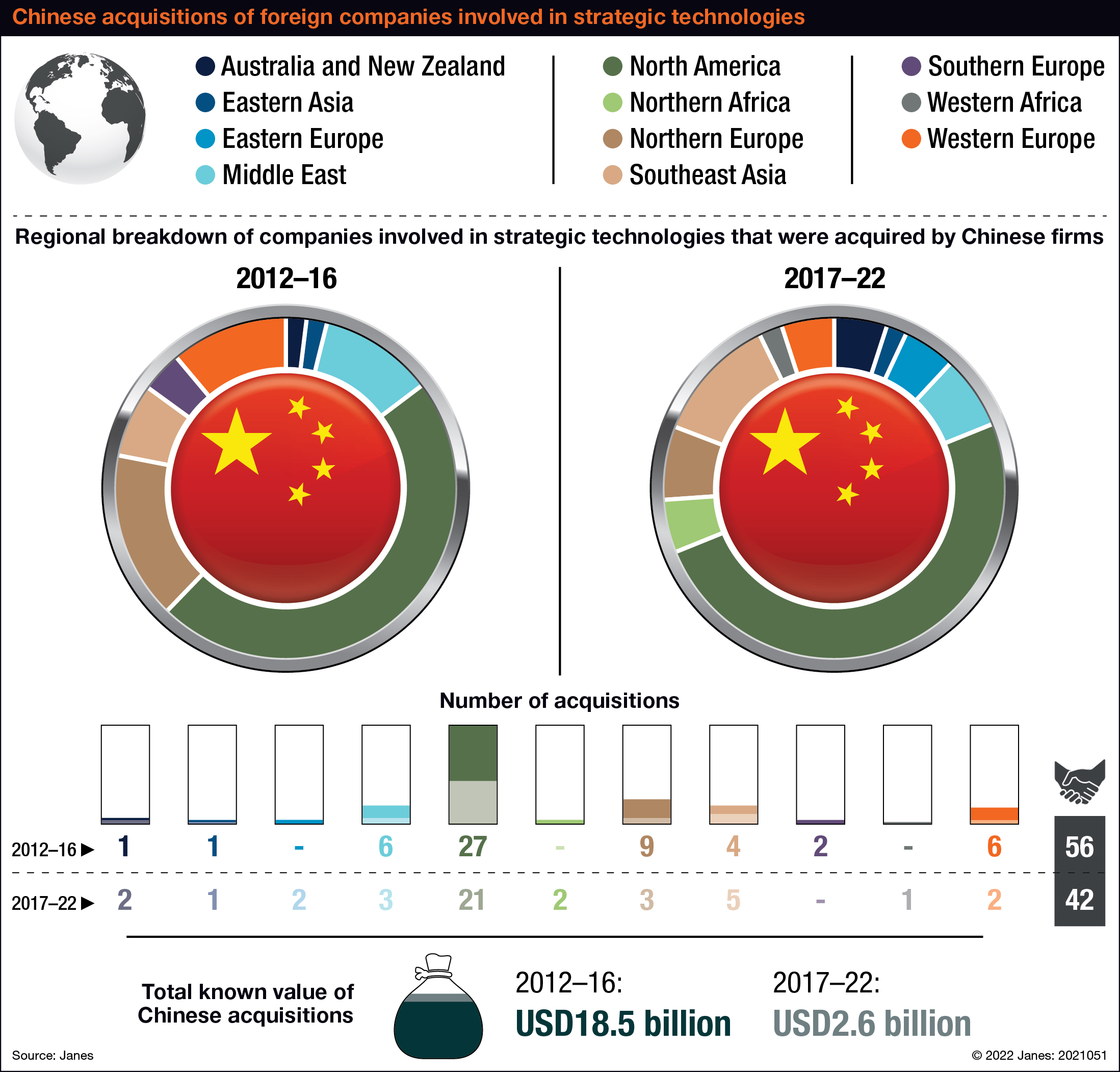

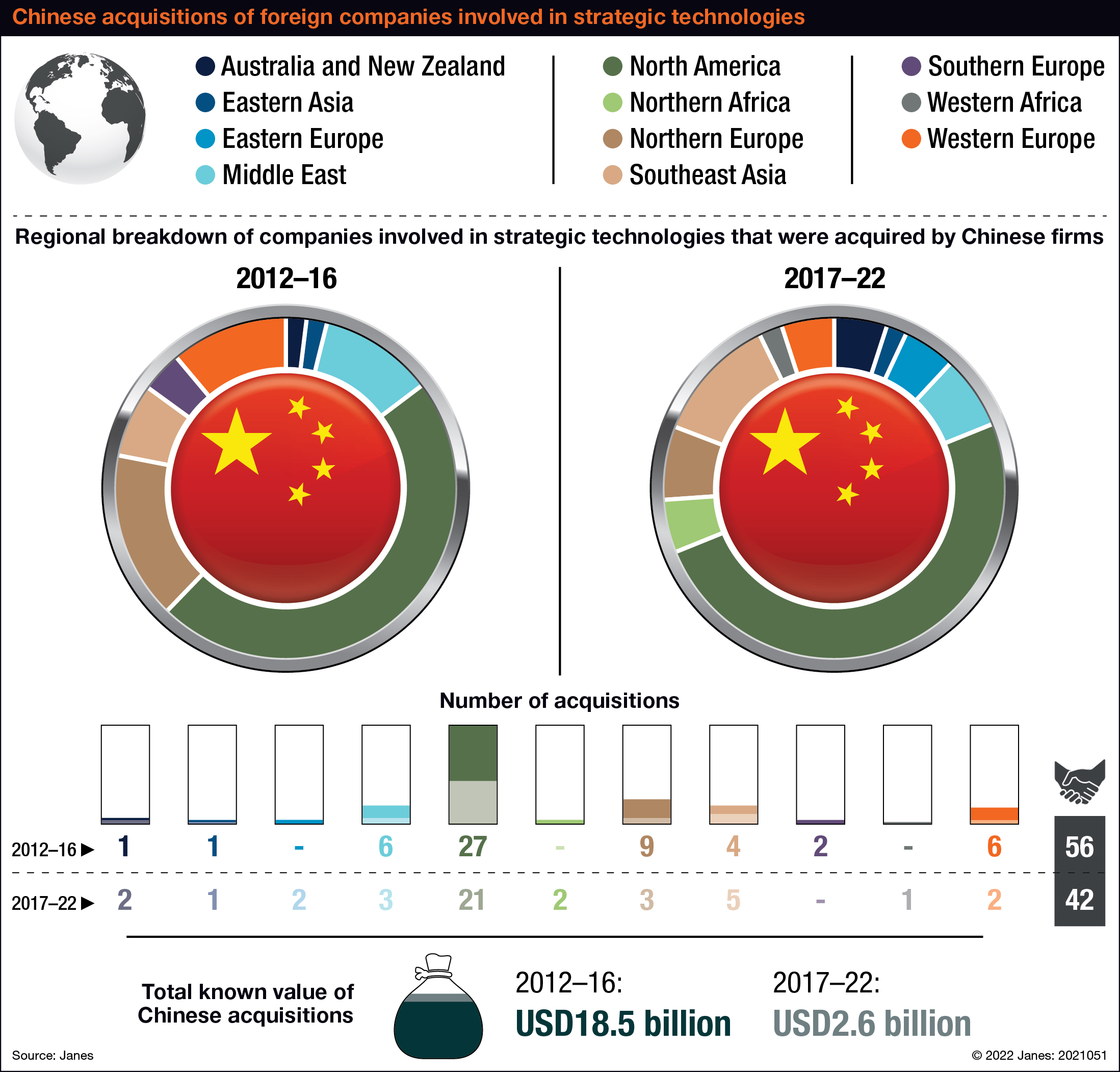

The vast majority of strategic technology firms acquired by Chinese investors are in North America, Janes data shows. (Janes IntelTrak)

Invest in the US

Janes IntelTrak data reveals that China's acquisitions of foreign companies that develop strategic technologies has been mainly focused on the US.

During 2012–16 nearly half of China's total 56 acquisitions were of companies in the US. During 2017–22 the number was 21, equal to exactly half.

In the earlier period, other popular target countries were Northern Europe (16%), Middle East (11%), and Western Europe (11%). In the latter period, the regional locations of target companies were more diversified and included a much larger portion of developing regions.

While half of Chinese acquisitions in strategic technology sectors in 2017–22 were located in the US, the other 50% were spread across regions including Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Northern Africa.

The Janes data also shows that most Chinese acquisitions of technology companies in these developing markets occurred since the start of the pandemic. Since 2020, Chinese investors have acquired or invested in just seven strategic-technology firms based in the US.

These firms include Plus and Nuro, both developers of autonomous logistics services, Medable (cloud services), International Data Group (data technologies), Flexiv (robotics), and Pony.ai (autonomous systems).

The nature of Chinese investments in foreign strategic-technology companies in recent years has also changed. Generally, they have become lower profile, involving smaller companies – often startups such as Nuro and Plus – meaning authorities are more likely to not notice transactions.

By contrast, several high-profile Chinese acquisitions were completed during 2012–16.

They included the Chongqing Helicopter Investment Corporation's acquisition of Enstrom Helicopters, a US company that produces military platforms, and China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation's (CASIC's) acquisition of Luxembourg-based IEE, a developer of sensors and related technologies.

CASIC was one of two state-owned Chinese defence enterprises that were active in acquiring overseas technology firms during 2012–16. The other was the Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC), which, during this period, acquired several foreign firms including Thielert Aircraft Engines from Germany, Thompson Aero Seating (UK), and Aim Altitude (UK). Earlier, during 2009–11, AVIC had taken over five overseas aerospace firms, with most of these in the US.

By contrast, during 2017–22 China's acquisitions of companies that develop strategic technologies have mainly featured private-sector Chinese firms and capital groups. The largest acquisition was in 2018 and featured Wanfeng Aviation's takeover of Austria-based Diamond Aircraft, whose products include special mission aircraft designed for operations including search and rescue, and coastal surveillance.

However, between 2013 and 2017 the reported value of acquisitions that were started within that time period was approximately USD18.5 billion. During 2017–22 the reported value, using the same timing metric, fell by 86% to USD2.6 billion.

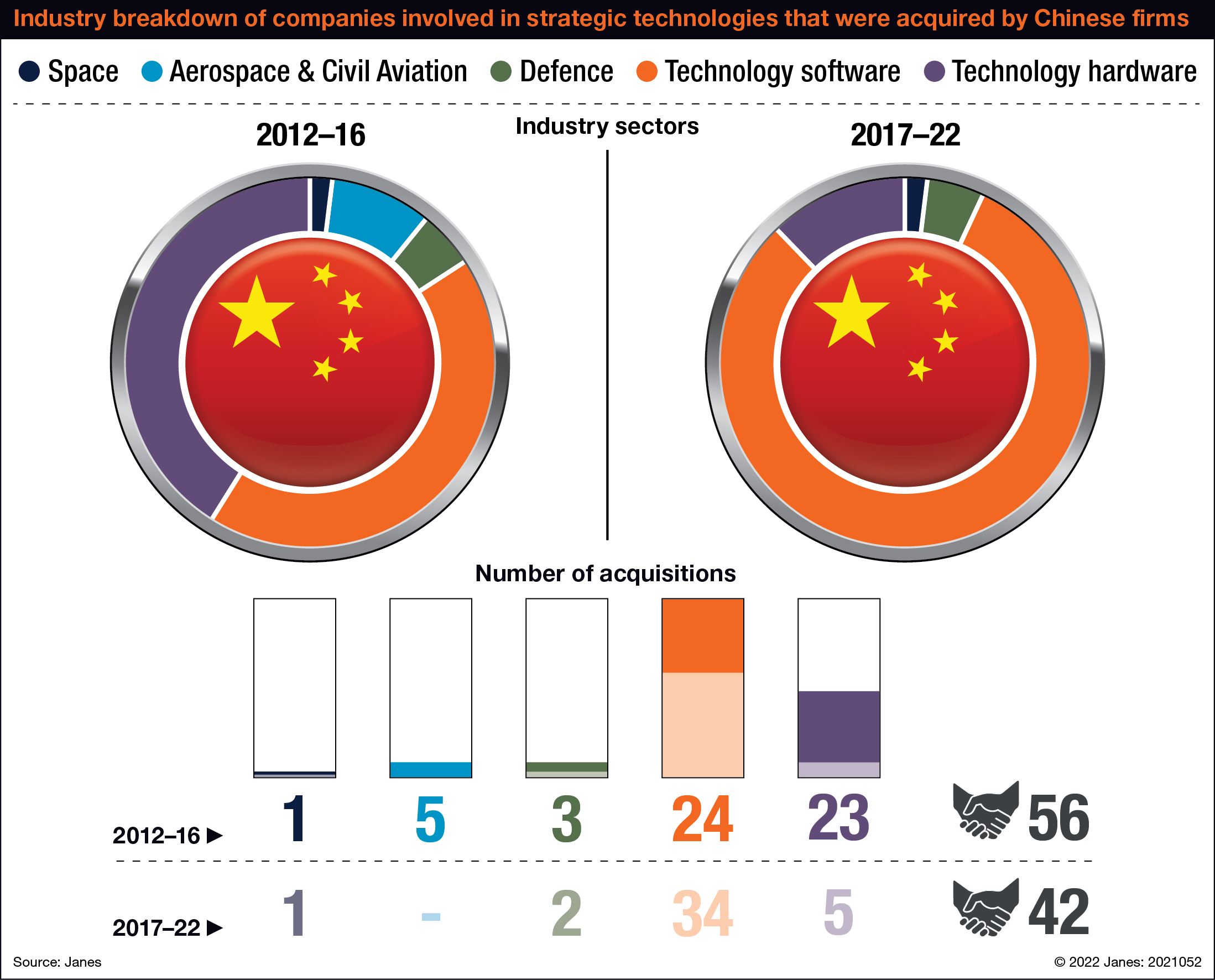

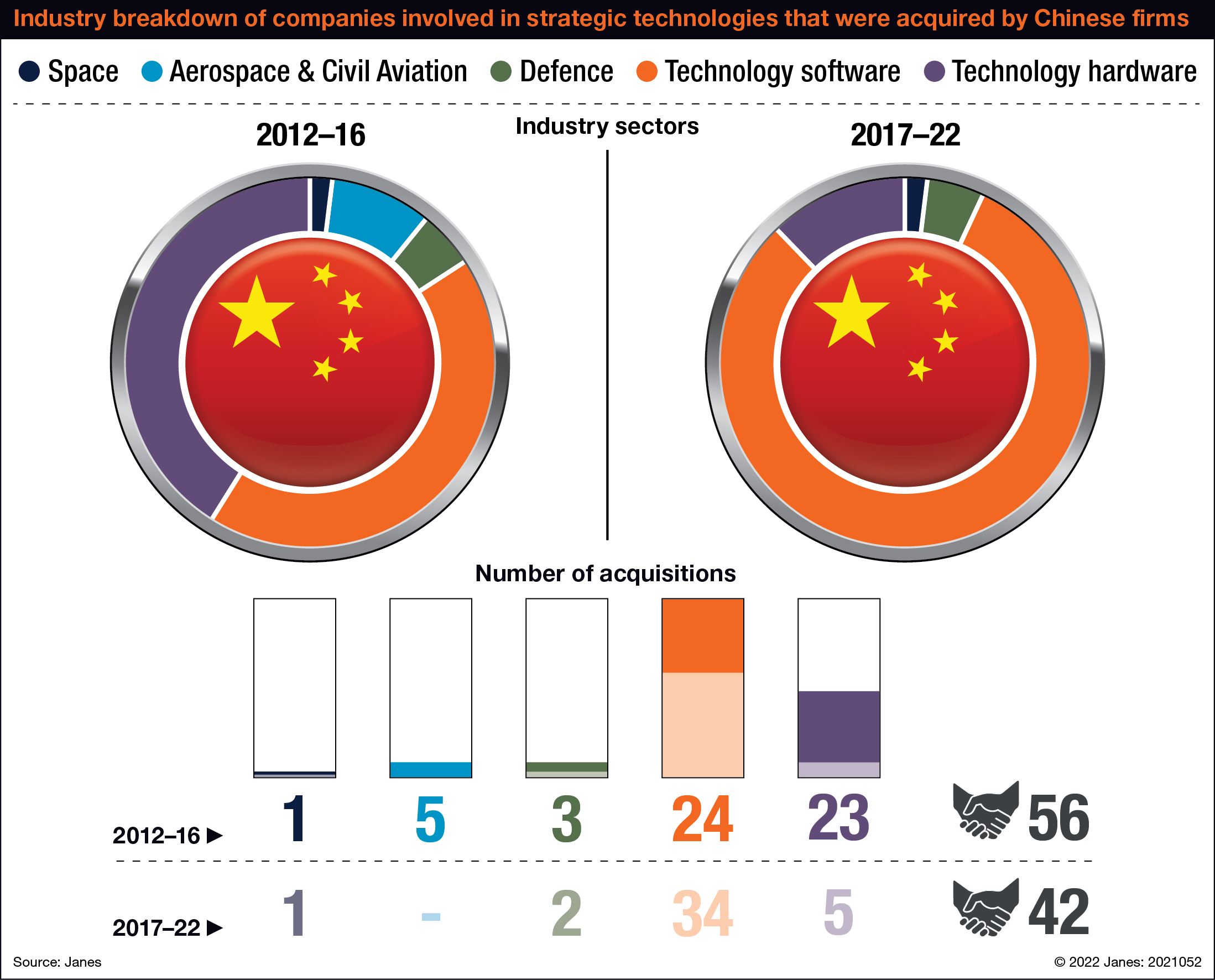

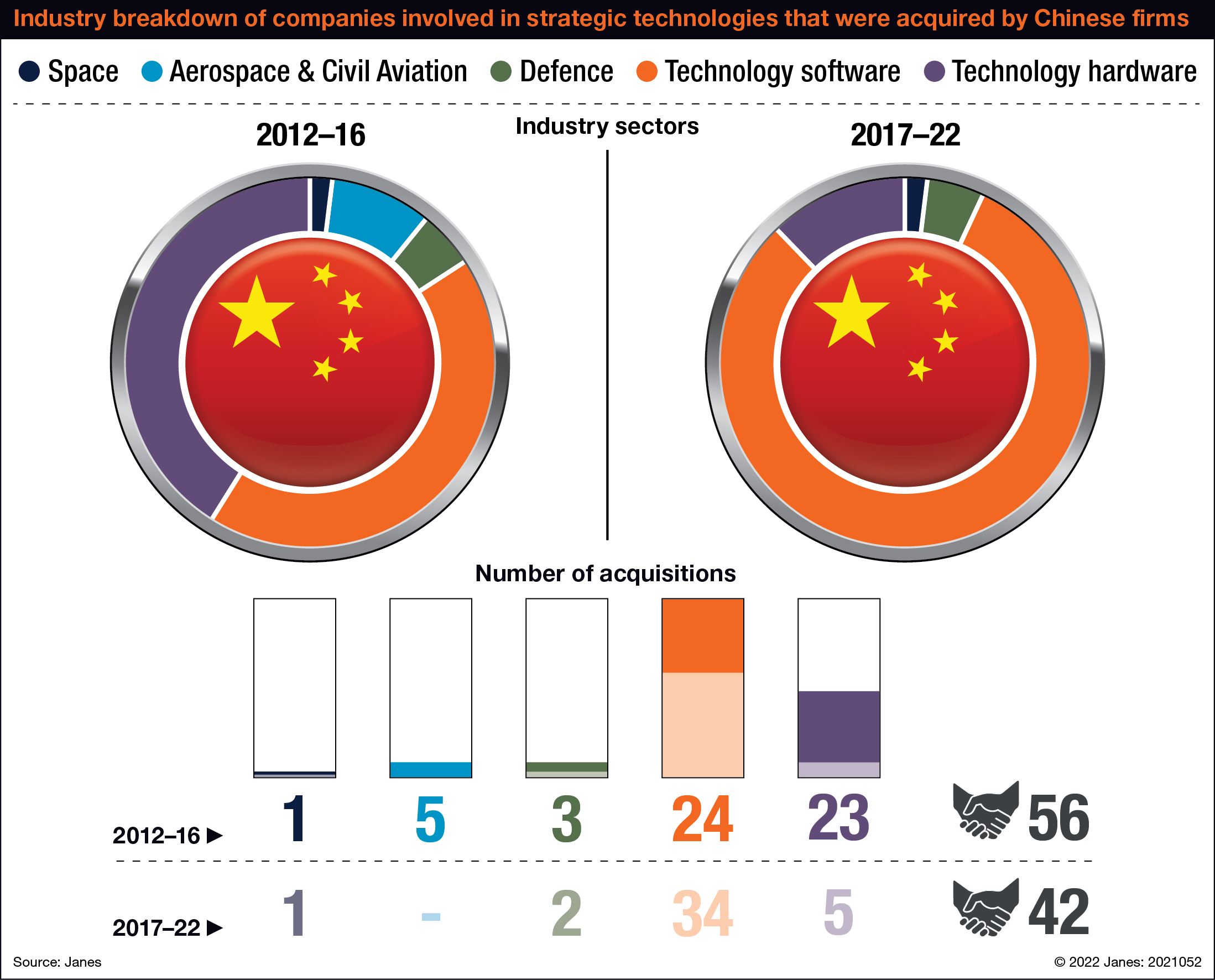

In the initial period, most of this Chinese investment was in foreign companies operating in technology products and services including semiconductors and software. Semiconductors, in particular, were clearly a focal point for Chinese acquisitions during 2013–17, with 13 foreign firms acquired, mainly in the US.

However, during 2017–22 the number of acquisitions that reported the value of the transaction fell to less than half the total number of deals. Most of these deals were similar in technology and software sectors, but, of note, included just one foreign company involved in the production of semiconductors: an Israeli firm named Camtek.

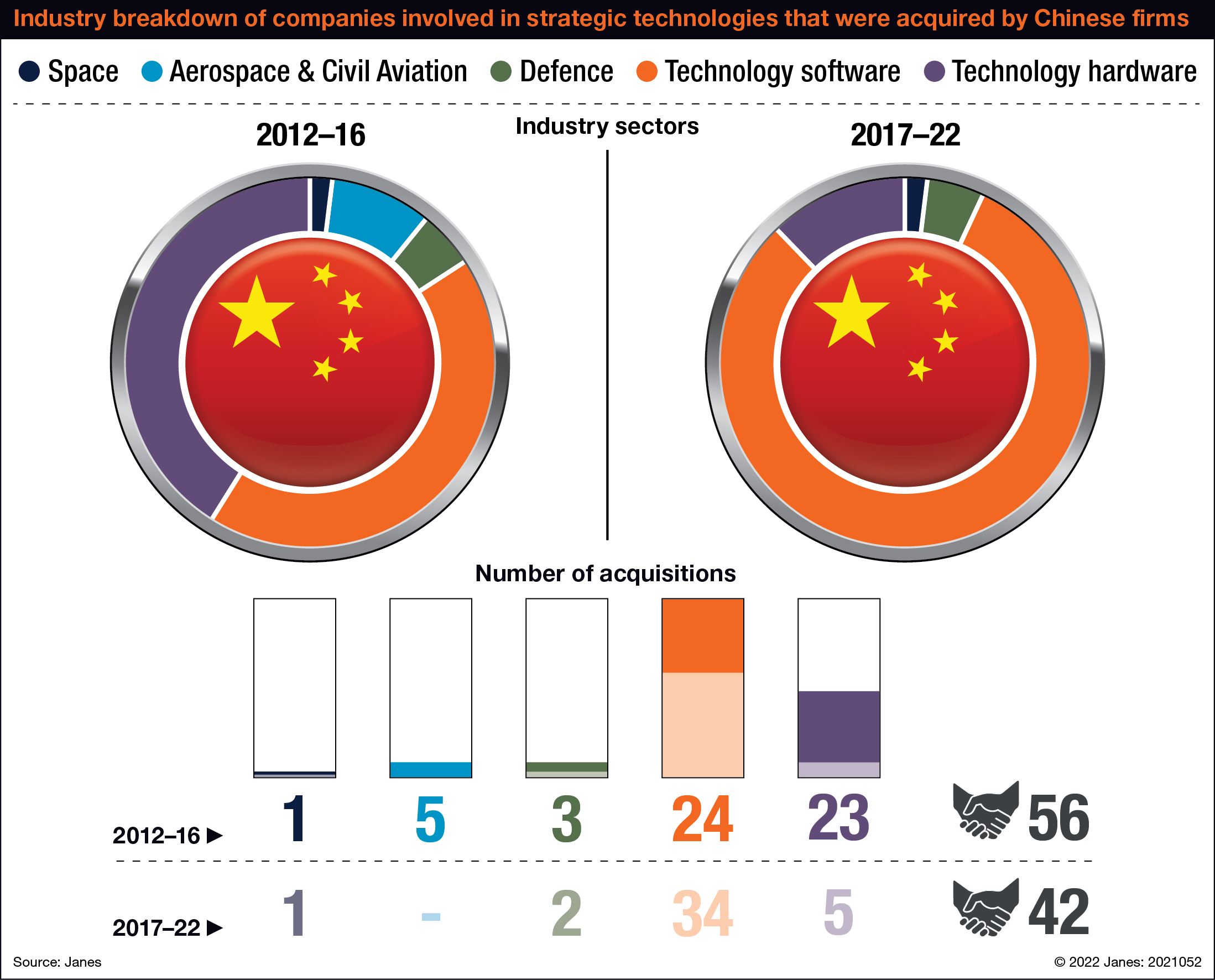

Foreign technology-software firms – involved in strategic technologies such as AI, robotics, autonomous systems, and cyber – have become increasingly popular for Chinese investors, Janes data shows. (Janes IntelTrak)

China's rationale

For Beijing, the acquisition of foreign strategic-technology companies and their capabilities plays a key role in supporting the development of the PLA.

The acquisition strategy has grown in significance for Beijing since the West imposed military sanctions on China in response to the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 in which, several thousand civilians were reported to be killed by the Chinese military.

The drive is also supported by several high-level policies in China intended to develop the country's global influence and build capability in both commercial and military domains. These include China's ‘Going out' strategy, the ‘Made in China 2025' policy, and President Xi Jinping's ‘Belt and Road Initiative'.

The corporate acquisition strategy has also been outwardly promoted by Beijing for years as part of a policy previously known as civil-military integration (CMI) but now called military-civil fusion (MCF) to reflect a requirement for a more intense combination of capabilities.

At its heart, MCF is focused at leveraging commercial technologies and techniques for military applications. Accordingly, MCF stands as a key Chinese method to acquire the technologies it needs to support military modernisation and overcome the long-standing sanctions.

In China's 14th Five Year Plan (FYP), which runs from 2021 to 2025, MCF received added impetus, reflecting China's efforts to accelerate military modernisation, especially in cutting-edge technologies it regards as ‘frontier' and ‘disruptive'.

In its priorities, the 14th FYP said that China would “accelerate the modernisation of weapons and equipment, [and] focus on independent innovation and original innovation in defence science and technology”.

The 14th FYP then went on to outline some of the methods that China intends to employ to achieve its military-technology and innovation priorities. Many of these methods are closely linked to MCF.

The five-year plan said, “[China] will deepen military-civilian science and technology collaboration and innovation, and strengthen the co-ordinated military-civilian development in maritime, space, cyberspace, biology, new energy, AI, quantum technology, etc to promote … the transformation and development of key industries.”

The 14th FYP went on to highlight how the MCF strategy will be applied during the 2021–25 period to also improve military capabilities in areas including technologies, infrastructure, logistics, training, mobilisation, and innovation.

It added, “[China will] optimise the structure of its defence science and technology industry … improve the national defence mobilisation system … strengthen national defence education … and consolidate military-civilian unity”.

However, China's acquisitions of foreign technology firms that can support this aim to achieve “military-civilian unity” is only one part of the MCF strategy.

The US Department of Defense (DoD) said in its 2021 report on China's military power that the strategy encompasses several methods to acquire foreign technologies, especially those in advanced commercial sectors such as AI and robotics.

“China uses imports, foreign investments, commercial joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions, and industrial and technical espionage to help achieve its military modernisation goals,” said the Pentagon report.

“The line demarcating products designed for commercial versus military use is blurring with these technologies.”

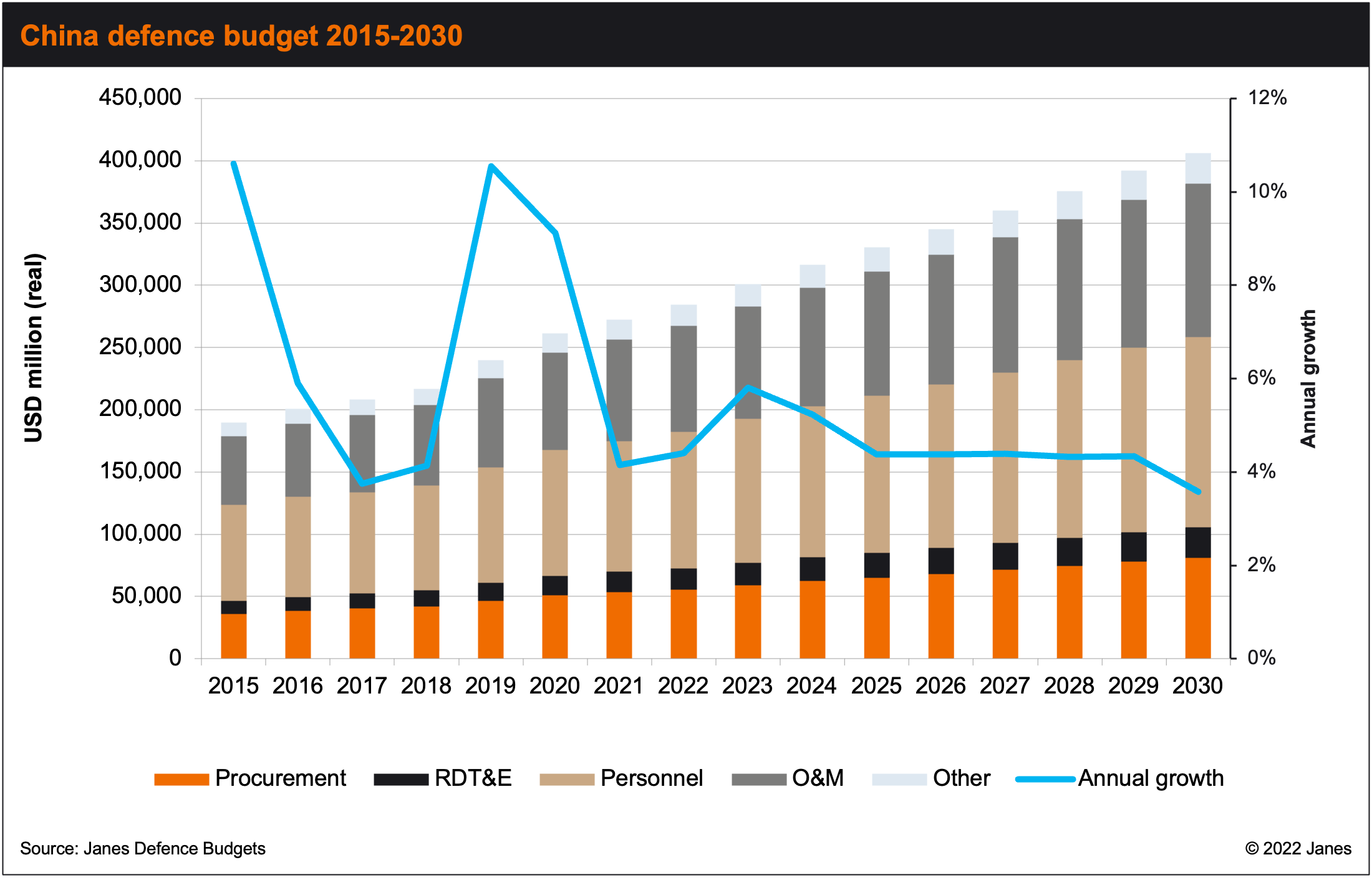

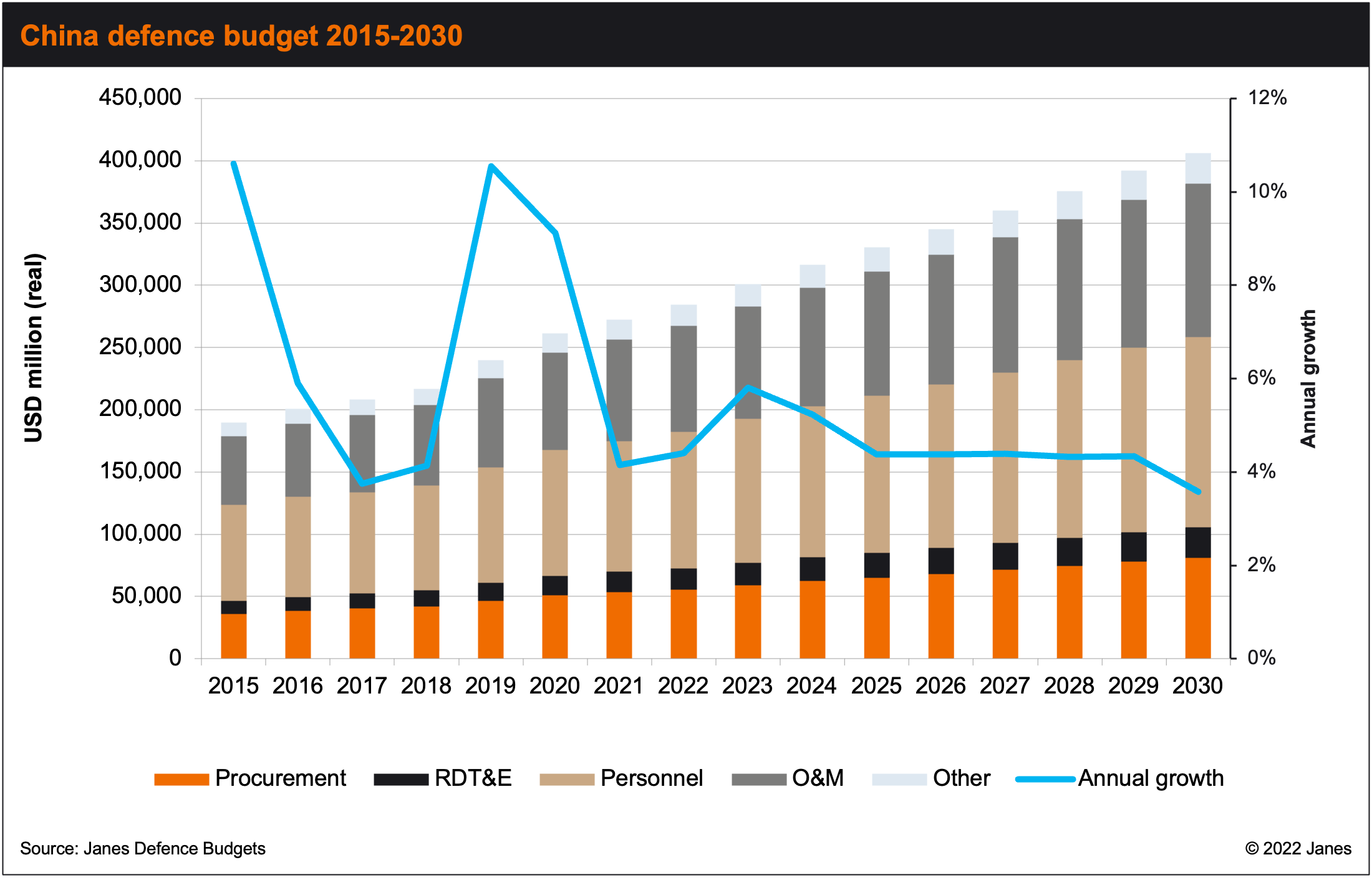

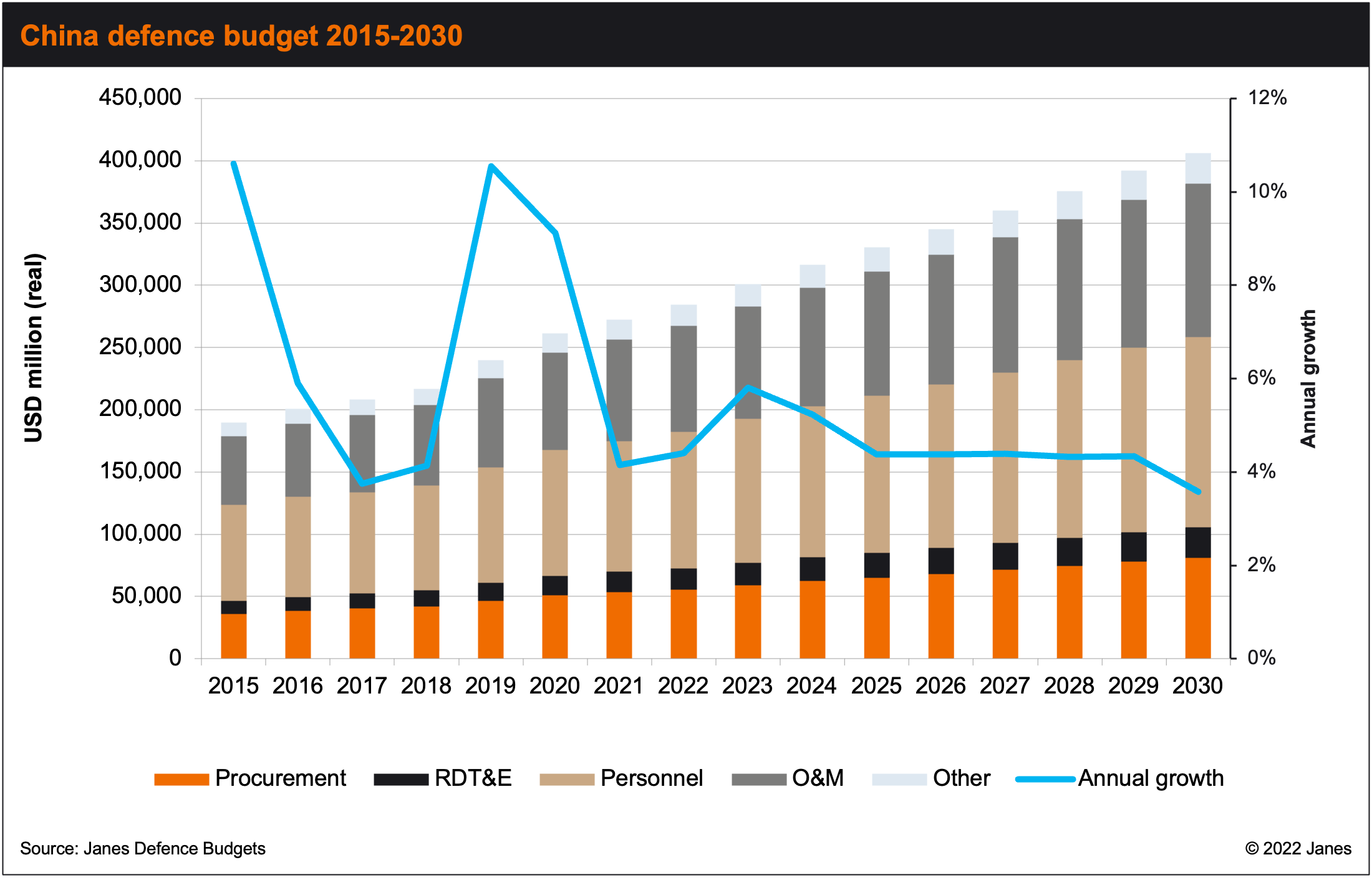

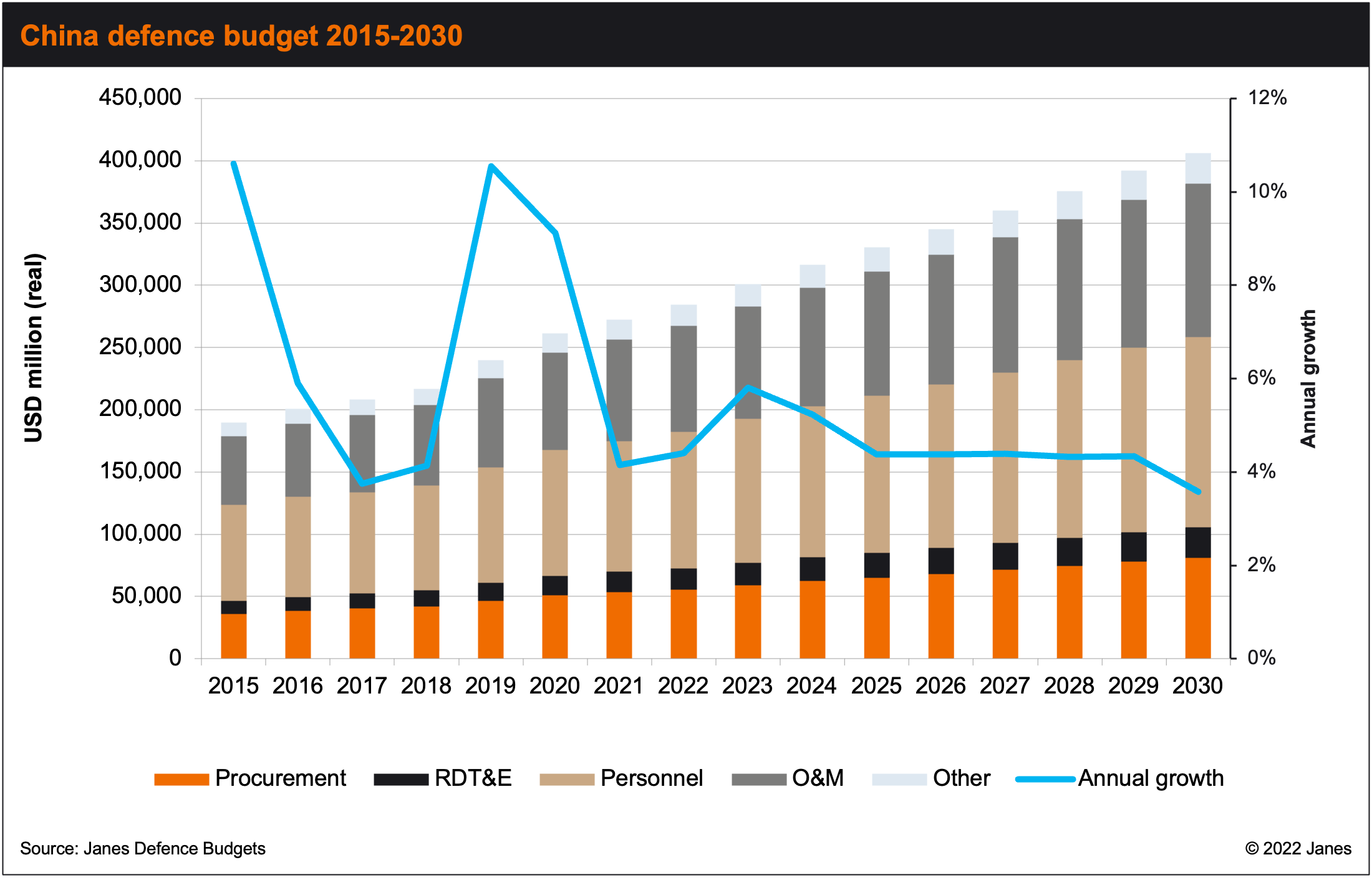

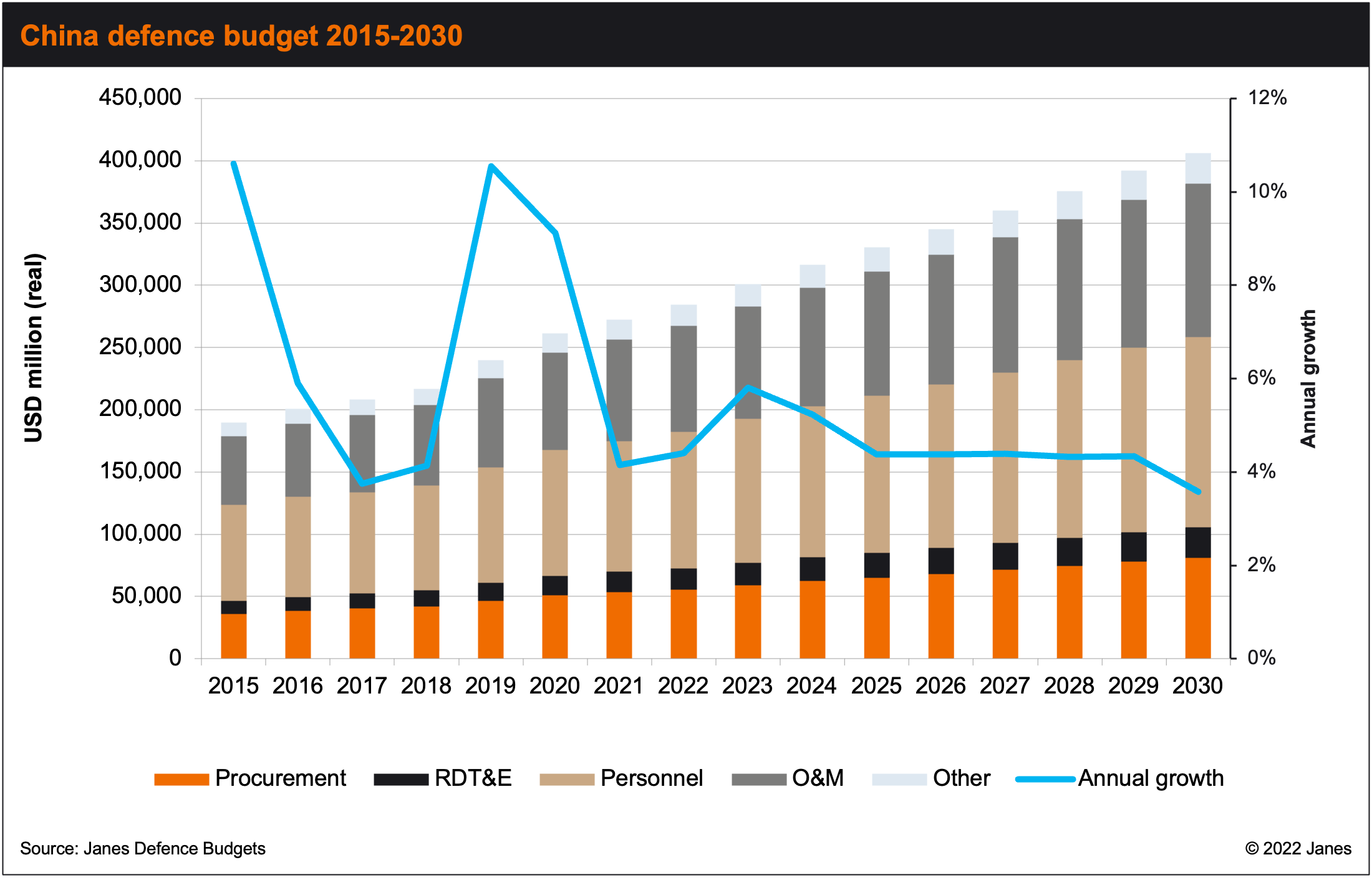

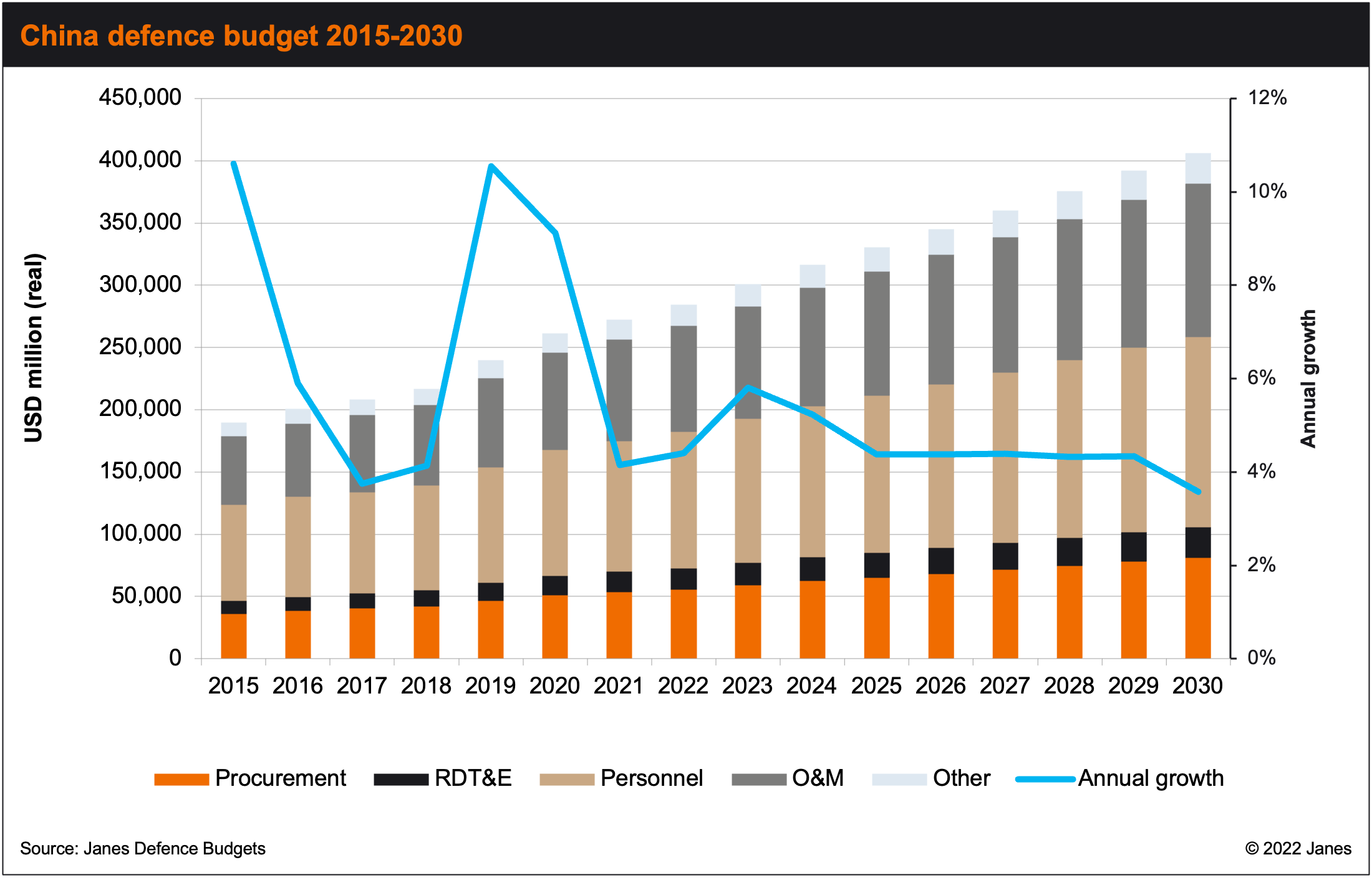

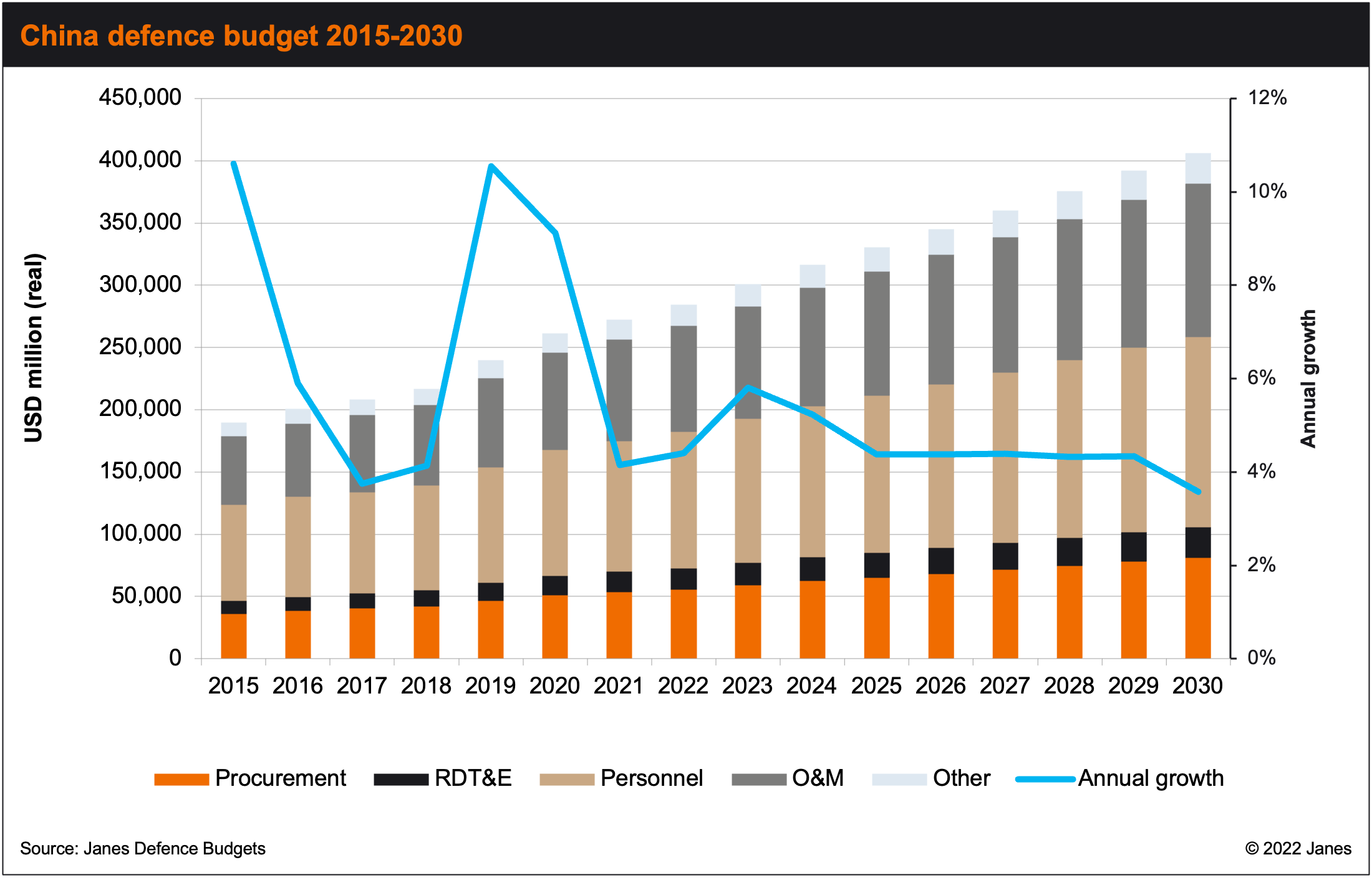

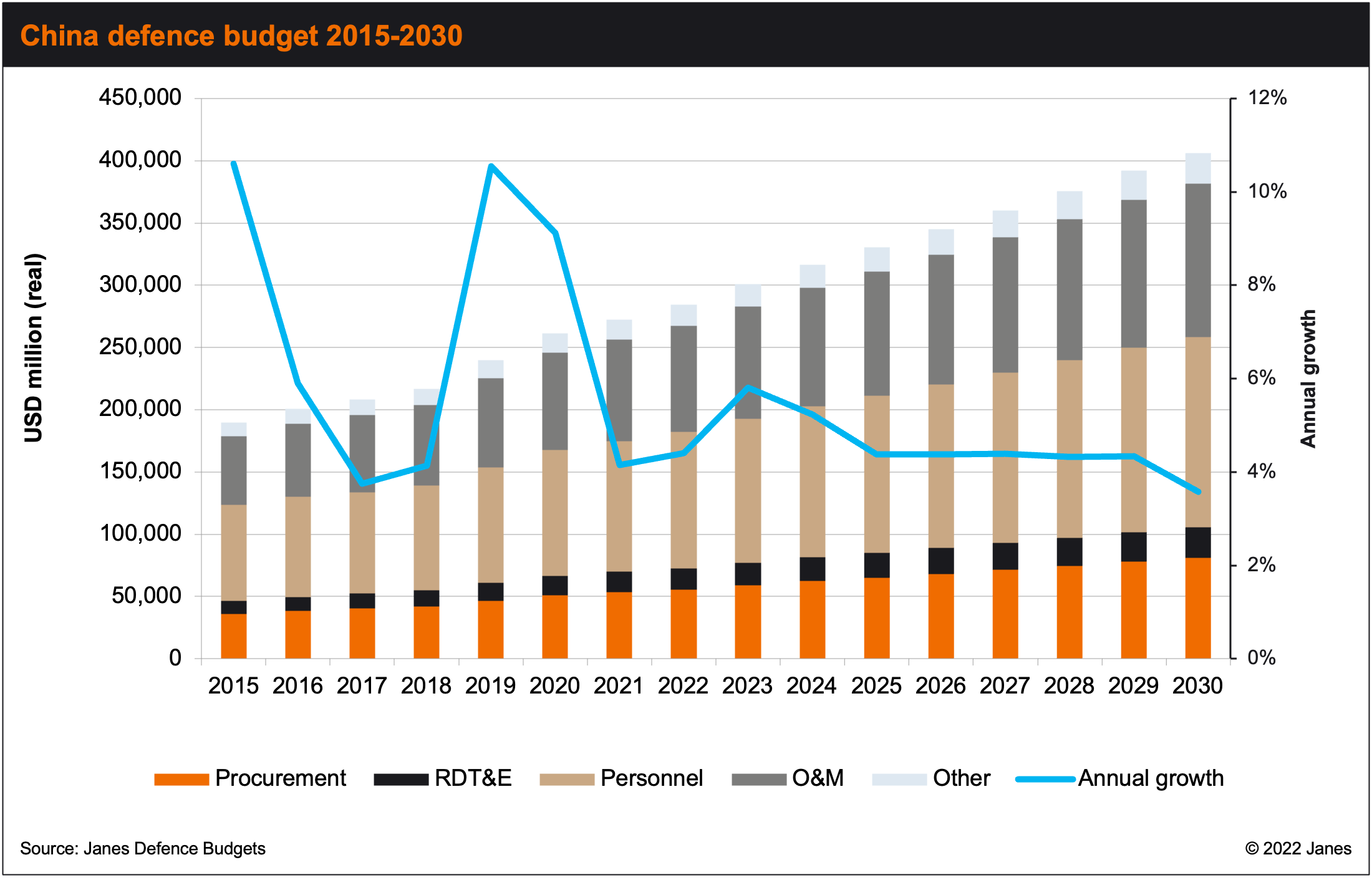

During China's 14th Five Year Plan (2021–25), Janes forecasts that China's total spending on defence will climb from the equivalent of USD272 billion to about USD331 billion. (Janes Defence Budgets)

Chinese acquisitions of foreign firms that develop strategic technologies are on the decline, Janes ...

Firm intentions: China's corporate acquisition strategy

18 July 2022

Chinese acquisitions of foreign firms that develop strategic technologies are on the decline, Janes data shows. Despite this, Beijing's strategy to support military gains through corporate takeovers remains a key part of its modernisation programme, Jon Grevatt reports

China's acquisitions of foreign firms that develop technologies that could benefit the People's Liberation Army (PLA) have declined in recent years, Janes IntelTrak data shows.

The decline is likely linked to increased international scrutiny of Chinese investment in local firms involved in these strategic sectors, which include aerospace, semiconductors, sensors, communications, navigation, robotics, and artificial intelligence (AI).

Despite this, Janes data also suggests that such corporate takeovers are likely to remain a crucial method for China in gaining access to foreign technologies in line with its increased emphasis on military-civil fusion (MCF).

During 2017–22 the number had declined by 25% to 42 foreign acquisitions. Again, most of these target firms were located in the US and involved in sectors such as visual recognition, AI, unmanned systems, Internet of things (IoT) technologies, semiconductors, navigation, and cartography.

In part, the difference between the two periods can be linked to variations in Chinese and foreign economies, which prompt firms periodically to either tighten their belts or look to secure inward investment.

However, it is the effort by foreign governments – including those in Australia, India, Japan, the US, and the United Kingdom – to ensure greater protection against investment from China in strategic technologies that is likely to have had the biggest impact on the Chinese acquisition strategy.

Many of these investment measures have been introduced since the start of Covid-19, with the goal to protect technology companies destabilised by the economic impact of the pandemic.

However, while concerns about Covid-19 are easing in many countries, it appears unlikely that such rules will be reverted given concerns held by many governments about China's strategic motives.

Such measures mean that China's private and state-owned companies face high barriers in their efforts to invest in or acquire foreign technology firms – especially those in the West – that are looking for such investment.

The vast majority of strategic technology firms acquired by Chinese investors are in North America, Janes data shows. (Janes IntelTrak)

Invest in the US

Janes IntelTrak data reveals that China's acquisitions of foreign companies that develop strategic technologies has been mainly focused on the US.

During 2012–16 nearly half of China's total 56 acquisitions were of companies in the US. During 2017–22 the number was 21, equal to exactly half.

In the earlier period, other popular target countries were Northern Europe (16%), Middle East (11%), and Western Europe (11%). In the latter period, the regional locations of target companies were more diversified and included a much larger portion of developing regions.

While half of Chinese acquisitions in strategic technology sectors in 2017–22 were located in the US, the other 50% were spread across regions including Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Northern Africa.

The Janes data also shows that most Chinese acquisitions of technology companies in these developing markets occurred since the start of the pandemic. Since 2020, Chinese investors have acquired or invested in just seven strategic-technology firms based in the US.

These firms include Plus and Nuro, both developers of autonomous logistics services, Medable (cloud services), International Data Group (data technologies), Flexiv (robotics), and Pony.ai (autonomous systems).

The nature of Chinese investments in foreign strategic-technology companies in recent years has also changed. Generally, they have become lower profile, involving smaller companies – often startups such as Nuro and Plus – meaning authorities are more likely to not notice transactions.

By contrast, several high-profile Chinese acquisitions were completed during 2012–16.

They included the Chongqing Helicopter Investment Corporation's acquisition of Enstrom Helicopters, a US company that produces military platforms, and China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation's (CASIC's) acquisition of Luxembourg-based IEE, a developer of sensors and related technologies.

CASIC was one of two state-owned Chinese defence enterprises that were active in acquiring overseas technology firms during 2012–16. The other was the Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC), which, during this period, acquired several foreign firms including Thielert Aircraft Engines from Germany, Thompson Aero Seating (UK), and Aim Altitude (UK). Earlier, during 2009–11, AVIC had taken over five overseas aerospace firms, with most of these in the US.

By contrast, during 2017–22 China's acquisitions of companies that develop strategic technologies have mainly featured private-sector Chinese firms and capital groups. The largest acquisition was in 2018 and featured Wanfeng Aviation's takeover of Austria-based Diamond Aircraft, whose products include special mission aircraft designed for operations including search and rescue, and coastal surveillance.

However, between 2013 and 2017 the reported value of acquisitions that were started within that time period was approximately USD18.5 billion. During 2017–22 the reported value, using the same timing metric, fell by 86% to USD2.6 billion.

In the initial period, most of this Chinese investment was in foreign companies operating in technology products and services including semiconductors and software. Semiconductors, in particular, were clearly a focal point for Chinese acquisitions during 2013–17, with 13 foreign firms acquired, mainly in the US.

However, during 2017–22 the number of acquisitions that reported the value of the transaction fell to less than half the total number of deals. Most of these deals were similar in technology and software sectors, but, of note, included just one foreign company involved in the production of semiconductors: an Israeli firm named Camtek.

Foreign technology-software firms – involved in strategic technologies such as AI, robotics, autonomous systems, and cyber – have become increasingly popular for Chinese investors, Janes data shows. (Janes IntelTrak)

China's rationale

For Beijing, the acquisition of foreign strategic-technology companies and their capabilities plays a key role in supporting the development of the PLA.

The acquisition strategy has grown in significance for Beijing since the West imposed military sanctions on China in response to the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 in which, several thousand civilians were reported to be killed by the Chinese military.

The drive is also supported by several high-level policies in China intended to develop the country's global influence and build capability in both commercial and military domains. These include China's ‘Going out' strategy, the ‘Made in China 2025' policy, and President Xi Jinping's ‘Belt and Road Initiative'.

The corporate acquisition strategy has also been outwardly promoted by Beijing for years as part of a policy previously known as civil-military integration (CMI) but now called military-civil fusion (MCF) to reflect a requirement for a more intense combination of capabilities.

At its heart, MCF is focused at leveraging commercial technologies and techniques for military applications. Accordingly, MCF stands as a key Chinese method to acquire the technologies it needs to support military modernisation and overcome the long-standing sanctions.

In China's 14th Five Year Plan (FYP), which runs from 2021 to 2025, MCF received added impetus, reflecting China's efforts to accelerate military modernisation, especially in cutting-edge technologies it regards as ‘frontier' and ‘disruptive'.

In its priorities, the 14th FYP said that China would “accelerate the modernisation of weapons and equipment, [and] focus on independent innovation and original innovation in defence science and technology”.

The 14th FYP then went on to outline some of the methods that China intends to employ to achieve its military-technology and innovation priorities. Many of these methods are closely linked to MCF.

The five-year plan said, “[China] will deepen military-civilian science and technology collaboration and innovation, and strengthen the co-ordinated military-civilian development in maritime, space, cyberspace, biology, new energy, AI, quantum technology, etc to promote … the transformation and development of key industries.”

The 14th FYP went on to highlight how the MCF strategy will be applied during the 2021–25 period to also improve military capabilities in areas including technologies, infrastructure, logistics, training, mobilisation, and innovation.

It added, “[China will] optimise the structure of its defence science and technology industry … improve the national defence mobilisation system … strengthen national defence education … and consolidate military-civilian unity”.

However, China's acquisitions of foreign technology firms that can support this aim to achieve “military-civilian unity” is only one part of the MCF strategy.

The US Department of Defense (DoD) said in its 2021 report on China's military power that the strategy encompasses several methods to acquire foreign technologies, especially those in advanced commercial sectors such as AI and robotics.

“China uses imports, foreign investments, commercial joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions, and industrial and technical espionage to help achieve its military modernisation goals,” said the Pentagon report.

“The line demarcating products designed for commercial versus military use is blurring with these technologies.”

During China's 14th Five Year Plan (2021–25), Janes forecasts that China's total spending on defence will climb from the equivalent of USD272 billion to about USD331 billion. (Janes Defence Budgets)

Chinese acquisitions of foreign firms that develop strategic technologies are on the decline, Janes ...

Firm intentions: China's corporate acquisition strategy

18 July 2022

Chinese acquisitions of foreign firms that develop strategic technologies are on the decline, Janes data shows. Despite this, Beijing's strategy to support military gains through corporate takeovers remains a key part of its modernisation programme, Jon Grevatt reports

China's acquisitions of foreign firms that develop technologies that could benefit the People's Liberation Army (PLA) have declined in recent years, Janes IntelTrak data shows.

The decline is likely linked to increased international scrutiny of Chinese investment in local firms involved in these strategic sectors, which include aerospace, semiconductors, sensors, communications, navigation, robotics, and artificial intelligence (AI).

Despite this, Janes data also suggests that such corporate takeovers are likely to remain a crucial method for China in gaining access to foreign technologies in line with its increased emphasis on military-civil fusion (MCF).

During 2017–22 the number had declined by 25% to 42 foreign acquisitions. Again, most of these target firms were located in the US and involved in sectors such as visual recognition, AI, unmanned systems, Internet of things (IoT) technologies, semiconductors, navigation, and cartography.

In part, the difference between the two periods can be linked to variations in Chinese and foreign economies, which prompt firms periodically to either tighten their belts or look to secure inward investment.

However, it is the effort by foreign governments – including those in Australia, India, Japan, the US, and the United Kingdom – to ensure greater protection against investment from China in strategic technologies that is likely to have had the biggest impact on the Chinese acquisition strategy.

Many of these investment measures have been introduced since the start of Covid-19, with the goal to protect technology companies destabilised by the economic impact of the pandemic.

However, while concerns about Covid-19 are easing in many countries, it appears unlikely that such rules will be reverted given concerns held by many governments about China's strategic motives.

Such measures mean that China's private and state-owned companies face high barriers in their efforts to invest in or acquire foreign technology firms – especially those in the West – that are looking for such investment.

The vast majority of strategic technology firms acquired by Chinese investors are in North America, Janes data shows. (Janes IntelTrak)

Invest in the US

Janes IntelTrak data reveals that China's acquisitions of foreign companies that develop strategic technologies has been mainly focused on the US.

During 2012–16 nearly half of China's total 56 acquisitions were of companies in the US. During 2017–22 the number was 21, equal to exactly half.

In the earlier period, other popular target countries were Northern Europe (16%), Middle East (11%), and Western Europe (11%). In the latter period, the regional locations of target companies were more diversified and included a much larger portion of developing regions.

While half of Chinese acquisitions in strategic technology sectors in 2017–22 were located in the US, the other 50% were spread across regions including Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Northern Africa.

The Janes data also shows that most Chinese acquisitions of technology companies in these developing markets occurred since the start of the pandemic. Since 2020, Chinese investors have acquired or invested in just seven strategic-technology firms based in the US.

These firms include Plus and Nuro, both developers of autonomous logistics services, Medable (cloud services), International Data Group (data technologies), Flexiv (robotics), and Pony.ai (autonomous systems).

The nature of Chinese investments in foreign strategic-technology companies in recent years has also changed. Generally, they have become lower profile, involving smaller companies – often startups such as Nuro and Plus – meaning authorities are more likely to not notice transactions.

By contrast, several high-profile Chinese acquisitions were completed during 2012–16.

They included the Chongqing Helicopter Investment Corporation's acquisition of Enstrom Helicopters, a US company that produces military platforms, and China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation's (CASIC's) acquisition of Luxembourg-based IEE, a developer of sensors and related technologies.

CASIC was one of two state-owned Chinese defence enterprises that were active in acquiring overseas technology firms during 2012–16. The other was the Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC), which, during this period, acquired several foreign firms including Thielert Aircraft Engines from Germany, Thompson Aero Seating (UK), and Aim Altitude (UK). Earlier, during 2009–11, AVIC had taken over five overseas aerospace firms, with most of these in the US.

By contrast, during 2017–22 China's acquisitions of companies that develop strategic technologies have mainly featured private-sector Chinese firms and capital groups. The largest acquisition was in 2018 and featured Wanfeng Aviation's takeover of Austria-based Diamond Aircraft, whose products include special mission aircraft designed for operations including search and rescue, and coastal surveillance.

However, between 2013 and 2017 the reported value of acquisitions that were started within that time period was approximately USD18.5 billion. During 2017–22 the reported value, using the same timing metric, fell by 86% to USD2.6 billion.

In the initial period, most of this Chinese investment was in foreign companies operating in technology products and services including semiconductors and software. Semiconductors, in particular, were clearly a focal point for Chinese acquisitions during 2013–17, with 13 foreign firms acquired, mainly in the US.

However, during 2017–22 the number of acquisitions that reported the value of the transaction fell to less than half the total number of deals. Most of these deals were similar in technology and software sectors, but, of note, included just one foreign company involved in the production of semiconductors: an Israeli firm named Camtek.

Foreign technology-software firms – involved in strategic technologies such as AI, robotics, autonomous systems, and cyber – have become increasingly popular for Chinese investors, Janes data shows. (Janes IntelTrak)

China's rationale

For Beijing, the acquisition of foreign strategic-technology companies and their capabilities plays a key role in supporting the development of the PLA.

The acquisition strategy has grown in significance for Beijing since the West imposed military sanctions on China in response to the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 in which, several thousand civilians were reported to be killed by the Chinese military.

The drive is also supported by several high-level policies in China intended to develop the country's global influence and build capability in both commercial and military domains. These include China's ‘Going out' strategy, the ‘Made in China 2025' policy, and President Xi Jinping's ‘Belt and Road Initiative'.

The corporate acquisition strategy has also been outwardly promoted by Beijing for years as part of a policy previously known as civil-military integration (CMI) but now called military-civil fusion (MCF) to reflect a requirement for a more intense combination of capabilities.

At its heart, MCF is focused at leveraging commercial technologies and techniques for military applications. Accordingly, MCF stands as a key Chinese method to acquire the technologies it needs to support military modernisation and overcome the long-standing sanctions.

In China's 14th Five Year Plan (FYP), which runs from 2021 to 2025, MCF received added impetus, reflecting China's efforts to accelerate military modernisation, especially in cutting-edge technologies it regards as ‘frontier' and ‘disruptive'.

In its priorities, the 14th FYP said that China would “accelerate the modernisation of weapons and equipment, [and] focus on independent innovation and original innovation in defence science and technology”.

The 14th FYP then went on to outline some of the methods that China intends to employ to achieve its military-technology and innovation priorities. Many of these methods are closely linked to MCF.

The five-year plan said, “[China] will deepen military-civilian science and technology collaboration and innovation, and strengthen the co-ordinated military-civilian development in maritime, space, cyberspace, biology, new energy, AI, quantum technology, etc to promote … the transformation and development of key industries.”

The 14th FYP went on to highlight how the MCF strategy will be applied during the 2021–25 period to also improve military capabilities in areas including technologies, infrastructure, logistics, training, mobilisation, and innovation.

It added, “[China will] optimise the structure of its defence science and technology industry … improve the national defence mobilisation system … strengthen national defence education … and consolidate military-civilian unity”.

However, China's acquisitions of foreign technology firms that can support this aim to achieve “military-civilian unity” is only one part of the MCF strategy.

The US Department of Defense (DoD) said in its 2021 report on China's military power that the strategy encompasses several methods to acquire foreign technologies, especially those in advanced commercial sectors such as AI and robotics.

“China uses imports, foreign investments, commercial joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions, and industrial and technical espionage to help achieve its military modernisation goals,” said the Pentagon report.

“The line demarcating products designed for commercial versus military use is blurring with these technologies.”

During China's 14th Five Year Plan (2021–25), Janes forecasts that China's total spending on defence will climb from the equivalent of USD272 billion to about USD331 billion. (Janes Defence Budgets)

Chinese acquisitions of foreign firms that develop strategic technologies are on the decline, Janes ...

Firm intentions: China's corporate acquisition strategy

18 July 2022

Chinese acquisitions of foreign firms that develop strategic technologies are on the decline, Janes data shows. Despite this, Beijing's strategy to support military gains through corporate takeovers remains a key part of its modernisation programme, Jon Grevatt reports

China's acquisitions of foreign firms that develop technologies that could benefit the People's Liberation Army (PLA) have declined in recent years, Janes IntelTrak data shows.

The decline is likely linked to increased international scrutiny of Chinese investment in local firms involved in these strategic sectors, which include aerospace, semiconductors, sensors, communications, navigation, robotics, and artificial intelligence (AI).

Despite this, Janes data also suggests that such corporate takeovers are likely to remain a crucial method for China in gaining access to foreign technologies in line with its increased emphasis on military-civil fusion (MCF).

During 2017–22 the number had declined by 25% to 42 foreign acquisitions. Again, most of these target firms were located in the US and involved in sectors such as visual recognition, AI, unmanned systems, Internet of things (IoT) technologies, semiconductors, navigation, and cartography.

In part, the difference between the two periods can be linked to variations in Chinese and foreign economies, which prompt firms periodically to either tighten their belts or look to secure inward investment.

However, it is the effort by foreign governments – including those in Australia, India, Japan, the US, and the United Kingdom – to ensure greater protection against investment from China in strategic technologies that is likely to have had the biggest impact on the Chinese acquisition strategy.

Many of these investment measures have been introduced since the start of Covid-19, with the goal to protect technology companies destabilised by the economic impact of the pandemic.

However, while concerns about Covid-19 are easing in many countries, it appears unlikely that such rules will be reverted given concerns held by many governments about China's strategic motives.

Such measures mean that China's private and state-owned companies face high barriers in their efforts to invest in or acquire foreign technology firms – especially those in the West – that are looking for such investment.

The vast majority of strategic technology firms acquired by Chinese investors are in North America, Janes data shows. (Janes IntelTrak)

Invest in the US

Janes IntelTrak data reveals that China's acquisitions of foreign companies that develop strategic technologies has been mainly focused on the US.

During 2012–16 nearly half of China's total 56 acquisitions were of companies in the US. During 2017–22 the number was 21, equal to exactly half.

In the earlier period, other popular target countries were Northern Europe (16%), Middle East (11%), and Western Europe (11%). In the latter period, the regional locations of target companies were more diversified and included a much larger portion of developing regions.

While half of Chinese acquisitions in strategic technology sectors in 2017–22 were located in the US, the other 50% were spread across regions including Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Northern Africa.

The Janes data also shows that most Chinese acquisitions of technology companies in these developing markets occurred since the start of the pandemic. Since 2020, Chinese investors have acquired or invested in just seven strategic-technology firms based in the US.

These firms include Plus and Nuro, both developers of autonomous logistics services, Medable (cloud services), International Data Group (data technologies), Flexiv (robotics), and Pony.ai (autonomous systems).

The nature of Chinese investments in foreign strategic-technology companies in recent years has also changed. Generally, they have become lower profile, involving smaller companies – often startups such as Nuro and Plus – meaning authorities are more likely to not notice transactions.

By contrast, several high-profile Chinese acquisitions were completed during 2012–16.

They included the Chongqing Helicopter Investment Corporation's acquisition of Enstrom Helicopters, a US company that produces military platforms, and China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation's (CASIC's) acquisition of Luxembourg-based IEE, a developer of sensors and related technologies.

CASIC was one of two state-owned Chinese defence enterprises that were active in acquiring overseas technology firms during 2012–16. The other was the Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC), which, during this period, acquired several foreign firms including Thielert Aircraft Engines from Germany, Thompson Aero Seating (UK), and Aim Altitude (UK). Earlier, during 2009–11, AVIC had taken over five overseas aerospace firms, with most of these in the US.

By contrast, during 2017–22 China's acquisitions of companies that develop strategic technologies have mainly featured private-sector Chinese firms and capital groups. The largest acquisition was in 2018 and featured Wanfeng Aviation's takeover of Austria-based Diamond Aircraft, whose products include special mission aircraft designed for operations including search and rescue, and coastal surveillance.

However, between 2013 and 2017 the reported value of acquisitions that were started within that time period was approximately USD18.5 billion. During 2017–22 the reported value, using the same timing metric, fell by 86% to USD2.6 billion.

In the initial period, most of this Chinese investment was in foreign companies operating in technology products and services including semiconductors and software. Semiconductors, in particular, were clearly a focal point for Chinese acquisitions during 2013–17, with 13 foreign firms acquired, mainly in the US.

However, during 2017–22 the number of acquisitions that reported the value of the transaction fell to less than half the total number of deals. Most of these deals were similar in technology and software sectors, but, of note, included just one foreign company involved in the production of semiconductors: an Israeli firm named Camtek.

Foreign technology-software firms – involved in strategic technologies such as AI, robotics, autonomous systems, and cyber – have become increasingly popular for Chinese investors, Janes data shows. (Janes IntelTrak)

China's rationale

For Beijing, the acquisition of foreign strategic-technology companies and their capabilities plays a key role in supporting the development of the PLA.

The acquisition strategy has grown in significance for Beijing since the West imposed military sanctions on China in response to the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 in which, several thousand civilians were reported to be killed by the Chinese military.

The drive is also supported by several high-level policies in China intended to develop the country's global influence and build capability in both commercial and military domains. These include China's ‘Going out' strategy, the ‘Made in China 2025' policy, and President Xi Jinping's ‘Belt and Road Initiative'.

The corporate acquisition strategy has also been outwardly promoted by Beijing for years as part of a policy previously known as civil-military integration (CMI) but now called military-civil fusion (MCF) to reflect a requirement for a more intense combination of capabilities.

At its heart, MCF is focused at leveraging commercial technologies and techniques for military applications. Accordingly, MCF stands as a key Chinese method to acquire the technologies it needs to support military modernisation and overcome the long-standing sanctions.

In China's 14th Five Year Plan (FYP), which runs from 2021 to 2025, MCF received added impetus, reflecting China's efforts to accelerate military modernisation, especially in cutting-edge technologies it regards as ‘frontier' and ‘disruptive'.

In its priorities, the 14th FYP said that China would “accelerate the modernisation of weapons and equipment, [and] focus on independent innovation and original innovation in defence science and technology”.

The 14th FYP then went on to outline some of the methods that China intends to employ to achieve its military-technology and innovation priorities. Many of these methods are closely linked to MCF.

The five-year plan said, “[China] will deepen military-civilian science and technology collaboration and innovation, and strengthen the co-ordinated military-civilian development in maritime, space, cyberspace, biology, new energy, AI, quantum technology, etc to promote … the transformation and development of key industries.”

The 14th FYP went on to highlight how the MCF strategy will be applied during the 2021–25 period to also improve military capabilities in areas including technologies, infrastructure, logistics, training, mobilisation, and innovation.

It added, “[China will] optimise the structure of its defence science and technology industry … improve the national defence mobilisation system … strengthen national defence education … and consolidate military-civilian unity”.

However, China's acquisitions of foreign technology firms that can support this aim to achieve “military-civilian unity” is only one part of the MCF strategy.

The US Department of Defense (DoD) said in its 2021 report on China's military power that the strategy encompasses several methods to acquire foreign technologies, especially those in advanced commercial sectors such as AI and robotics.

“China uses imports, foreign investments, commercial joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions, and industrial and technical espionage to help achieve its military modernisation goals,” said the Pentagon report.

“The line demarcating products designed for commercial versus military use is blurring with these technologies.”

During China's 14th Five Year Plan (2021–25), Janes forecasts that China's total spending on defence will climb from the equivalent of USD272 billion to about USD331 billion. (Janes Defence Budgets)

Chinese acquisitions of foreign firms that develop strategic technologies are on the decline, Janes ...

Firm intentions: China's corporate acquisition strategy

18 July 2022

Chinese acquisitions of foreign firms that develop strategic technologies are on the decline, Janes data shows. Despite this, Beijing's strategy to support military gains through corporate takeovers remains a key part of its modernisation programme, Jon Grevatt reports

China's acquisitions of foreign firms that develop technologies that could benefit the People's Liberation Army (PLA) have declined in recent years, Janes IntelTrak data shows.

The decline is likely linked to increased international scrutiny of Chinese investment in local firms involved in these strategic sectors, which include aerospace, semiconductors, sensors, communications, navigation, robotics, and artificial intelligence (AI).

Despite this, Janes data also suggests that such corporate takeovers are likely to remain a crucial method for China in gaining access to foreign technologies in line with its increased emphasis on military-civil fusion (MCF).

During 2017–22 the number had declined by 25% to 42 foreign acquisitions. Again, most of these target firms were located in the US and involved in sectors such as visual recognition, AI, unmanned systems, Internet of things (IoT) technologies, semiconductors, navigation, and cartography.

In part, the difference between the two periods can be linked to variations in Chinese and foreign economies, which prompt firms periodically to either tighten their belts or look to secure inward investment.

However, it is the effort by foreign governments – including those in Australia, India, Japan, the US, and the United Kingdom – to ensure greater protection against investment from China in strategic technologies that is likely to have had the biggest impact on the Chinese acquisition strategy.

Many of these investment measures have been introduced since the start of Covid-19, with the goal to protect technology companies destabilised by the economic impact of the pandemic.

However, while concerns about Covid-19 are easing in many countries, it appears unlikely that such rules will be reverted given concerns held by many governments about China's strategic motives.

Such measures mean that China's private and state-owned companies face high barriers in their efforts to invest in or acquire foreign technology firms – especially those in the West – that are looking for such investment.

The vast majority of strategic technology firms acquired by Chinese investors are in North America, Janes data shows. (Janes IntelTrak)

Invest in the US

Janes IntelTrak data reveals that China's acquisitions of foreign companies that develop strategic technologies has been mainly focused on the US.

During 2012–16 nearly half of China's total 56 acquisitions were of companies in the US. During 2017–22 the number was 21, equal to exactly half.

In the earlier period, other popular target countries were Northern Europe (16%), Middle East (11%), and Western Europe (11%). In the latter period, the regional locations of target companies were more diversified and included a much larger portion of developing regions.

While half of Chinese acquisitions in strategic technology sectors in 2017–22 were located in the US, the other 50% were spread across regions including Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Northern Africa.

The Janes data also shows that most Chinese acquisitions of technology companies in these developing markets occurred since the start of the pandemic. Since 2020, Chinese investors have acquired or invested in just seven strategic-technology firms based in the US.

These firms include Plus and Nuro, both developers of autonomous logistics services, Medable (cloud services), International Data Group (data technologies), Flexiv (robotics), and Pony.ai (autonomous systems).

The nature of Chinese investments in foreign strategic-technology companies in recent years has also changed. Generally, they have become lower profile, involving smaller companies – often startups such as Nuro and Plus – meaning authorities are more likely to not notice transactions.

By contrast, several high-profile Chinese acquisitions were completed during 2012–16.

They included the Chongqing Helicopter Investment Corporation's acquisition of Enstrom Helicopters, a US company that produces military platforms, and China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation's (CASIC's) acquisition of Luxembourg-based IEE, a developer of sensors and related technologies.

CASIC was one of two state-owned Chinese defence enterprises that were active in acquiring overseas technology firms during 2012–16. The other was the Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC), which, during this period, acquired several foreign firms including Thielert Aircraft Engines from Germany, Thompson Aero Seating (UK), and Aim Altitude (UK). Earlier, during 2009–11, AVIC had taken over five overseas aerospace firms, with most of these in the US.

By contrast, during 2017–22 China's acquisitions of companies that develop strategic technologies have mainly featured private-sector Chinese firms and capital groups. The largest acquisition was in 2018 and featured Wanfeng Aviation's takeover of Austria-based Diamond Aircraft, whose products include special mission aircraft designed for operations including search and rescue, and coastal surveillance.

However, between 2013 and 2017 the reported value of acquisitions that were started within that time period was approximately USD18.5 billion. During 2017–22 the reported value, using the same timing metric, fell by 86% to USD2.6 billion.

In the initial period, most of this Chinese investment was in foreign companies operating in technology products and services including semiconductors and software. Semiconductors, in particular, were clearly a focal point for Chinese acquisitions during 2013–17, with 13 foreign firms acquired, mainly in the US.

However, during 2017–22 the number of acquisitions that reported the value of the transaction fell to less than half the total number of deals. Most of these deals were similar in technology and software sectors, but, of note, included just one foreign company involved in the production of semiconductors: an Israeli firm named Camtek.

Foreign technology-software firms – involved in strategic technologies such as AI, robotics, autonomous systems, and cyber – have become increasingly popular for Chinese investors, Janes data shows. (Janes IntelTrak)

China's rationale

For Beijing, the acquisition of foreign strategic-technology companies and their capabilities plays a key role in supporting the development of the PLA.

The acquisition strategy has grown in significance for Beijing since the West imposed military sanctions on China in response to the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 in which, several thousand civilians were reported to be killed by the Chinese military.

The drive is also supported by several high-level policies in China intended to develop the country's global influence and build capability in both commercial and military domains. These include China's ‘Going out' strategy, the ‘Made in China 2025' policy, and President Xi Jinping's ‘Belt and Road Initiative'.

The corporate acquisition strategy has also been outwardly promoted by Beijing for years as part of a policy previously known as civil-military integration (CMI) but now called military-civil fusion (MCF) to reflect a requirement for a more intense combination of capabilities.

At its heart, MCF is focused at leveraging commercial technologies and techniques for military applications. Accordingly, MCF stands as a key Chinese method to acquire the technologies it needs to support military modernisation and overcome the long-standing sanctions.

In China's 14th Five Year Plan (FYP), which runs from 2021 to 2025, MCF received added impetus, reflecting China's efforts to accelerate military modernisation, especially in cutting-edge technologies it regards as ‘frontier' and ‘disruptive'.

In its priorities, the 14th FYP said that China would “accelerate the modernisation of weapons and equipment, [and] focus on independent innovation and original innovation in defence science and technology”.

The 14th FYP then went on to outline some of the methods that China intends to employ to achieve its military-technology and innovation priorities. Many of these methods are closely linked to MCF.

The five-year plan said, “[China] will deepen military-civilian science and technology collaboration and innovation, and strengthen the co-ordinated military-civilian development in maritime, space, cyberspace, biology, new energy, AI, quantum technology, etc to promote … the transformation and development of key industries.”

The 14th FYP went on to highlight how the MCF strategy will be applied during the 2021–25 period to also improve military capabilities in areas including technologies, infrastructure, logistics, training, mobilisation, and innovation.

It added, “[China will] optimise the structure of its defence science and technology industry … improve the national defence mobilisation system … strengthen national defence education … and consolidate military-civilian unity”.

However, China's acquisitions of foreign technology firms that can support this aim to achieve “military-civilian unity” is only one part of the MCF strategy.

The US Department of Defense (DoD) said in its 2021 report on China's military power that the strategy encompasses several methods to acquire foreign technologies, especially those in advanced commercial sectors such as AI and robotics.

“China uses imports, foreign investments, commercial joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions, and industrial and technical espionage to help achieve its military modernisation goals,” said the Pentagon report.

“The line demarcating products designed for commercial versus military use is blurring with these technologies.”

During China's 14th Five Year Plan (2021–25), Janes forecasts that China's total spending on defence will climb from the equivalent of USD272 billion to about USD331 billion. (Janes Defence Budgets)

Chinese acquisitions of foreign firms that develop strategic technologies are on the decline, Janes ...

Firm intentions: China's corporate acquisition strategy

18 July 2022

Chinese acquisitions of foreign firms that develop strategic technologies are on the decline, Janes data shows. Despite this, Beijing's strategy to support military gains through corporate takeovers remains a key part of its modernisation programme, Jon Grevatt reports

China's acquisitions of foreign firms that develop technologies that could benefit the People's Liberation Army (PLA) have declined in recent years, Janes IntelTrak data shows.

The decline is likely linked to increased international scrutiny of Chinese investment in local firms involved in these strategic sectors, which include aerospace, semiconductors, sensors, communications, navigation, robotics, and artificial intelligence (AI).

Despite this, Janes data also suggests that such corporate takeovers are likely to remain a crucial method for China in gaining access to foreign technologies in line with its increased emphasis on military-civil fusion (MCF).

During 2017–22 the number had declined by 25% to 42 foreign acquisitions. Again, most of these target firms were located in the US and involved in sectors such as visual recognition, AI, unmanned systems, Internet of things (IoT) technologies, semiconductors, navigation, and cartography.

In part, the difference between the two periods can be linked to variations in Chinese and foreign economies, which prompt firms periodically to either tighten their belts or look to secure inward investment.

However, it is the effort by foreign governments – including those in Australia, India, Japan, the US, and the United Kingdom – to ensure greater protection against investment from China in strategic technologies that is likely to have had the biggest impact on the Chinese acquisition strategy.

Many of these investment measures have been introduced since the start of Covid-19, with the goal to protect technology companies destabilised by the economic impact of the pandemic.

However, while concerns about Covid-19 are easing in many countries, it appears unlikely that such rules will be reverted given concerns held by many governments about China's strategic motives.

Such measures mean that China's private and state-owned companies face high barriers in their efforts to invest in or acquire foreign technology firms – especially those in the West – that are looking for such investment.

The vast majority of strategic technology firms acquired by Chinese investors are in North America, Janes data shows. (Janes IntelTrak)

Invest in the US

Janes IntelTrak data reveals that China's acquisitions of foreign companies that develop strategic technologies has been mainly focused on the US.

During 2012–16 nearly half of China's total 56 acquisitions were of companies in the US. During 2017–22 the number was 21, equal to exactly half.

In the earlier period, other popular target countries were Northern Europe (16%), Middle East (11%), and Western Europe (11%). In the latter period, the regional locations of target companies were more diversified and included a much larger portion of developing regions.

While half of Chinese acquisitions in strategic technology sectors in 2017–22 were located in the US, the other 50% were spread across regions including Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Northern Africa.

The Janes data also shows that most Chinese acquisitions of technology companies in these developing markets occurred since the start of the pandemic. Since 2020, Chinese investors have acquired or invested in just seven strategic-technology firms based in the US.

These firms include Plus and Nuro, both developers of autonomous logistics services, Medable (cloud services), International Data Group (data technologies), Flexiv (robotics), and Pony.ai (autonomous systems).

The nature of Chinese investments in foreign strategic-technology companies in recent years has also changed. Generally, they have become lower profile, involving smaller companies – often startups such as Nuro and Plus – meaning authorities are more likely to not notice transactions.

By contrast, several high-profile Chinese acquisitions were completed during 2012–16.

They included the Chongqing Helicopter Investment Corporation's acquisition of Enstrom Helicopters, a US company that produces military platforms, and China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation's (CASIC's) acquisition of Luxembourg-based IEE, a developer of sensors and related technologies.

CASIC was one of two state-owned Chinese defence enterprises that were active in acquiring overseas technology firms during 2012–16. The other was the Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC), which, during this period, acquired several foreign firms including Thielert Aircraft Engines from Germany, Thompson Aero Seating (UK), and Aim Altitude (UK). Earlier, during 2009–11, AVIC had taken over five overseas aerospace firms, with most of these in the US.

By contrast, during 2017–22 China's acquisitions of companies that develop strategic technologies have mainly featured private-sector Chinese firms and capital groups. The largest acquisition was in 2018 and featured Wanfeng Aviation's takeover of Austria-based Diamond Aircraft, whose products include special mission aircraft designed for operations including search and rescue, and coastal surveillance.

However, between 2013 and 2017 the reported value of acquisitions that were started within that time period was approximately USD18.5 billion. During 2017–22 the reported value, using the same timing metric, fell by 86% to USD2.6 billion.

In the initial period, most of this Chinese investment was in foreign companies operating in technology products and services including semiconductors and software. Semiconductors, in particular, were clearly a focal point for Chinese acquisitions during 2013–17, with 13 foreign firms acquired, mainly in the US.

However, during 2017–22 the number of acquisitions that reported the value of the transaction fell to less than half the total number of deals. Most of these deals were similar in technology and software sectors, but, of note, included just one foreign company involved in the production of semiconductors: an Israeli firm named Camtek.

Foreign technology-software firms – involved in strategic technologies such as AI, robotics, autonomous systems, and cyber – have become increasingly popular for Chinese investors, Janes data shows. (Janes IntelTrak)

China's rationale

For Beijing, the acquisition of foreign strategic-technology companies and their capabilities plays a key role in supporting the development of the PLA.

The acquisition strategy has grown in significance for Beijing since the West imposed military sanctions on China in response to the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 in which, several thousand civilians were reported to be killed by the Chinese military.

The drive is also supported by several high-level policies in China intended to develop the country's global influence and build capability in both commercial and military domains. These include China's ‘Going out' strategy, the ‘Made in China 2025' policy, and President Xi Jinping's ‘Belt and Road Initiative'.

The corporate acquisition strategy has also been outwardly promoted by Beijing for years as part of a policy previously known as civil-military integration (CMI) but now called military-civil fusion (MCF) to reflect a requirement for a more intense combination of capabilities.

At its heart, MCF is focused at leveraging commercial technologies and techniques for military applications. Accordingly, MCF stands as a key Chinese method to acquire the technologies it needs to support military modernisation and overcome the long-standing sanctions.

In China's 14th Five Year Plan (FYP), which runs from 2021 to 2025, MCF received added impetus, reflecting China's efforts to accelerate military modernisation, especially in cutting-edge technologies it regards as ‘frontier' and ‘disruptive'.

In its priorities, the 14th FYP said that China would “accelerate the modernisation of weapons and equipment, [and] focus on independent innovation and original innovation in defence science and technology”.

The 14th FYP then went on to outline some of the methods that China intends to employ to achieve its military-technology and innovation priorities. Many of these methods are closely linked to MCF.

The five-year plan said, “[China] will deepen military-civilian science and technology collaboration and innovation, and strengthen the co-ordinated military-civilian development in maritime, space, cyberspace, biology, new energy, AI, quantum technology, etc to promote … the transformation and development of key industries.”

The 14th FYP went on to highlight how the MCF strategy will be applied during the 2021–25 period to also improve military capabilities in areas including technologies, infrastructure, logistics, training, mobilisation, and innovation.

It added, “[China will] optimise the structure of its defence science and technology industry … improve the national defence mobilisation system … strengthen national defence education … and consolidate military-civilian unity”.

However, China's acquisitions of foreign technology firms that can support this aim to achieve “military-civilian unity” is only one part of the MCF strategy.

The US Department of Defense (DoD) said in its 2021 report on China's military power that the strategy encompasses several methods to acquire foreign technologies, especially those in advanced commercial sectors such as AI and robotics.

“China uses imports, foreign investments, commercial joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions, and industrial and technical espionage to help achieve its military modernisation goals,” said the Pentagon report.

“The line demarcating products designed for commercial versus military use is blurring with these technologies.”

During China's 14th Five Year Plan (2021–25), Janes forecasts that China's total spending on defence will climb from the equivalent of USD272 billion to about USD331 billion. (Janes Defence Budgets)

Chinese acquisitions of foreign firms that develop strategic technologies are on the decline, Janes ...

Firm intentions: China's corporate acquisition strategy

18 July 2022

Chinese acquisitions of foreign firms that develop strategic technologies are on the decline, Janes data shows. Despite this, Beijing's strategy to support military gains through corporate takeovers remains a key part of its modernisation programme, Jon Grevatt reports

China's acquisitions of foreign firms that develop technologies that could benefit the People's Liberation Army (PLA) have declined in recent years, Janes IntelTrak data shows.

The decline is likely linked to increased international scrutiny of Chinese investment in local firms involved in these strategic sectors, which include aerospace, semiconductors, sensors, communications, navigation, robotics, and artificial intelligence (AI).

Despite this, Janes data also suggests that such corporate takeovers are likely to remain a crucial method for China in gaining access to foreign technologies in line with its increased emphasis on military-civil fusion (MCF).

During 2017–22 the number had declined by 25% to 42 foreign acquisitions. Again, most of these target firms were located in the US and involved in sectors such as visual recognition, AI, unmanned systems, Internet of things (IoT) technologies, semiconductors, navigation, and cartography.

In part, the difference between the two periods can be linked to variations in Chinese and foreign economies, which prompt firms periodically to either tighten their belts or look to secure inward investment.

However, it is the effort by foreign governments – including those in Australia, India, Japan, the US, and the United Kingdom – to ensure greater protection against investment from China in strategic technologies that is likely to have had the biggest impact on the Chinese acquisition strategy.

Many of these investment measures have been introduced since the start of Covid-19, with the goal to protect technology companies destabilised by the economic impact of the pandemic.

However, while concerns about Covid-19 are easing in many countries, it appears unlikely that such rules will be reverted given concerns held by many governments about China's strategic motives.

Such measures mean that China's private and state-owned companies face high barriers in their efforts to invest in or acquire foreign technology firms – especially those in the West – that are looking for such investment.

The vast majority of strategic technology firms acquired by Chinese investors are in North America, Janes data shows. (Janes IntelTrak)

Invest in the US

Janes IntelTrak data reveals that China's acquisitions of foreign companies that develop strategic technologies has been mainly focused on the US.

During 2012–16 nearly half of China's total 56 acquisitions were of companies in the US. During 2017–22 the number was 21, equal to exactly half.

In the earlier period, other popular target countries were Northern Europe (16%), Middle East (11%), and Western Europe (11%). In the latter period, the regional locations of target companies were more diversified and included a much larger portion of developing regions.

While half of Chinese acquisitions in strategic technology sectors in 2017–22 were located in the US, the other 50% were spread across regions including Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Northern Africa.

The Janes data also shows that most Chinese acquisitions of technology companies in these developing markets occurred since the start of the pandemic. Since 2020, Chinese investors have acquired or invested in just seven strategic-technology firms based in the US.

These firms include Plus and Nuro, both developers of autonomous logistics services, Medable (cloud services), International Data Group (data technologies), Flexiv (robotics), and Pony.ai (autonomous systems).

The nature of Chinese investments in foreign strategic-technology companies in recent years has also changed. Generally, they have become lower profile, involving smaller companies – often startups such as Nuro and Plus – meaning authorities are more likely to not notice transactions.

By contrast, several high-profile Chinese acquisitions were completed during 2012–16.

They included the Chongqing Helicopter Investment Corporation's acquisition of Enstrom Helicopters, a US company that produces military platforms, and China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation's (CASIC's) acquisition of Luxembourg-based IEE, a developer of sensors and related technologies.

CASIC was one of two state-owned Chinese defence enterprises that were active in acquiring overseas technology firms during 2012–16. The other was the Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC), which, during this period, acquired several foreign firms including Thielert Aircraft Engines from Germany, Thompson Aero Seating (UK), and Aim Altitude (UK). Earlier, during 2009–11, AVIC had taken over five overseas aerospace firms, with most of these in the US.

By contrast, during 2017–22 China's acquisitions of companies that develop strategic technologies have mainly featured private-sector Chinese firms and capital groups. The largest acquisition was in 2018 and featured Wanfeng Aviation's takeover of Austria-based Diamond Aircraft, whose products include special mission aircraft designed for operations including search and rescue, and coastal surveillance.

However, between 2013 and 2017 the reported value of acquisitions that were started within that time period was approximately USD18.5 billion. During 2017–22 the reported value, using the same timing metric, fell by 86% to USD2.6 billion.

In the initial period, most of this Chinese investment was in foreign companies operating in technology products and services including semiconductors and software. Semiconductors, in particular, were clearly a focal point for Chinese acquisitions during 2013–17, with 13 foreign firms acquired, mainly in the US.

However, during 2017–22 the number of acquisitions that reported the value of the transaction fell to less than half the total number of deals. Most of these deals were similar in technology and software sectors, but, of note, included just one foreign company involved in the production of semiconductors: an Israeli firm named Camtek.

Foreign technology-software firms – involved in strategic technologies such as AI, robotics, autonomous systems, and cyber – have become increasingly popular for Chinese investors, Janes data shows. (Janes IntelTrak)

China's rationale

For Beijing, the acquisition of foreign strategic-technology companies and their capabilities plays a key role in supporting the development of the PLA.

The acquisition strategy has grown in significance for Beijing since the West imposed military sanctions on China in response to the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 in which, several thousand civilians were reported to be killed by the Chinese military.

The drive is also supported by several high-level policies in China intended to develop the country's global influence and build capability in both commercial and military domains. These include China's ‘Going out' strategy, the ‘Made in China 2025' policy, and President Xi Jinping's ‘Belt and Road Initiative'.

The corporate acquisition strategy has also been outwardly promoted by Beijing for years as part of a policy previously known as civil-military integration (CMI) but now called military-civil fusion (MCF) to reflect a requirement for a more intense combination of capabilities.

At its heart, MCF is focused at leveraging commercial technologies and techniques for military applications. Accordingly, MCF stands as a key Chinese method to acquire the technologies it needs to support military modernisation and overcome the long-standing sanctions.

In China's 14th Five Year Plan (FYP), which runs from 2021 to 2025, MCF received added impetus, reflecting China's efforts to accelerate military modernisation, especially in cutting-edge technologies it regards as ‘frontier' and ‘disruptive'.

In its priorities, the 14th FYP said that China would “accelerate the modernisation of weapons and equipment, [and] focus on independent innovation and original innovation in defence science and technology”.

The 14th FYP then went on to outline some of the methods that China intends to employ to achieve its military-technology and innovation priorities. Many of these methods are closely linked to MCF.

The five-year plan said, “[China] will deepen military-civilian science and technology collaboration and innovation, and strengthen the co-ordinated military-civilian development in maritime, space, cyberspace, biology, new energy, AI, quantum technology, etc to promote … the transformation and development of key industries.”

The 14th FYP went on to highlight how the MCF strategy will be applied during the 2021–25 period to also improve military capabilities in areas including technologies, infrastructure, logistics, training, mobilisation, and innovation.

It added, “[China will] optimise the structure of its defence science and technology industry … improve the national defence mobilisation system … strengthen national defence education … and consolidate military-civilian unity”.

However, China's acquisitions of foreign technology firms that can support this aim to achieve “military-civilian unity” is only one part of the MCF strategy.

The US Department of Defense (DoD) said in its 2021 report on China's military power that the strategy encompasses several methods to acquire foreign technologies, especially those in advanced commercial sectors such as AI and robotics.

“China uses imports, foreign investments, commercial joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions, and industrial and technical espionage to help achieve its military modernisation goals,” said the Pentagon report.

“The line demarcating products designed for commercial versus military use is blurring with these technologies.”

During China's 14th Five Year Plan (2021–25), Janes forecasts that China's total spending on defence will climb from the equivalent of USD272 billion to about USD331 billion. (Janes Defence Budgets)

Chinese acquisitions of foreign firms that develop strategic technologies are on the decline, Janes ...

Firm intentions: China's corporate acquisition strategy

18 July 2022

Chinese acquisitions of foreign firms that develop strategic technologies are on the decline, Janes data shows. Despite this, Beijing's strategy to support military gains through corporate takeovers remains a key part of its modernisation programme, Jon Grevatt reports

China's acquisitions of foreign firms that develop technologies that could benefit the People's Liberation Army (PLA) have declined in recent years, Janes IntelTrak data shows.

The decline is likely linked to increased international scrutiny of Chinese investment in local firms involved in these strategic sectors, which include aerospace, semiconductors, sensors, communications, navigation, robotics, and artificial intelligence (AI).

Despite this, Janes data also suggests that such corporate takeovers are likely to remain a crucial method for China in gaining access to foreign technologies in line with its increased emphasis on military-civil fusion (MCF).

During 2017–22 the number had declined by 25% to 42 foreign acquisitions. Again, most of these target firms were located in the US and involved in sectors such as visual recognition, AI, unmanned systems, Internet of things (IoT) technologies, semiconductors, navigation, and cartography.

In part, the difference between the two periods can be linked to variations in Chinese and foreign economies, which prompt firms periodically to either tighten their belts or look to secure inward investment.

However, it is the effort by foreign governments – including those in Australia, India, Japan, the US, and the United Kingdom – to ensure greater protection against investment from China in strategic technologies that is likely to have had the biggest impact on the Chinese acquisition strategy.

Many of these investment measures have been introduced since the start of Covid-19, with the goal to protect technology companies destabilised by the economic impact of the pandemic.

However, while concerns about Covid-19 are easing in many countries, it appears unlikely that such rules will be reverted given concerns held by many governments about China's strategic motives.

Such measures mean that China's private and state-owned companies face high barriers in their efforts to invest in or acquire foreign technology firms – especially those in the West – that are looking for such investment.

The vast majority of strategic technology firms acquired by Chinese investors are in North America, Janes data shows. (Janes IntelTrak)

Invest in the US

Janes IntelTrak data reveals that China's acquisitions of foreign companies that develop strategic technologies has been mainly focused on the US.

During 2012–16 nearly half of China's total 56 acquisitions were of companies in the US. During 2017–22 the number was 21, equal to exactly half.

In the earlier period, other popular target countries were Northern Europe (16%), Middle East (11%), and Western Europe (11%). In the latter period, the regional locations of target companies were more diversified and included a much larger portion of developing regions.

While half of Chinese acquisitions in strategic technology sectors in 2017–22 were located in the US, the other 50% were spread across regions including Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Northern Africa.

The Janes data also shows that most Chinese acquisitions of technology companies in these developing markets occurred since the start of the pandemic. Since 2020, Chinese investors have acquired or invested in just seven strategic-technology firms based in the US.

These firms include Plus and Nuro, both developers of autonomous logistics services, Medable (cloud services), International Data Group (data technologies), Flexiv (robotics), and Pony.ai (autonomous systems).

The nature of Chinese investments in foreign strategic-technology companies in recent years has also changed. Generally, they have become lower profile, involving smaller companies – often startups such as Nuro and Plus – meaning authorities are more likely to not notice transactions.

By contrast, several high-profile Chinese acquisitions were completed during 2012–16.

They included the Chongqing Helicopter Investment Corporation's acquisition of Enstrom Helicopters, a US company that produces military platforms, and China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation's (CASIC's) acquisition of Luxembourg-based IEE, a developer of sensors and related technologies.

CASIC was one of two state-owned Chinese defence enterprises that were active in acquiring overseas technology firms during 2012–16. The other was the Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC), which, during this period, acquired several foreign firms including Thielert Aircraft Engines from Germany, Thompson Aero Seating (UK), and Aim Altitude (UK). Earlier, during 2009–11, AVIC had taken over five overseas aerospace firms, with most of these in the US.

By contrast, during 2017–22 China's acquisitions of companies that develop strategic technologies have mainly featured private-sector Chinese firms and capital groups. The largest acquisition was in 2018 and featured Wanfeng Aviation's takeover of Austria-based Diamond Aircraft, whose products include special mission aircraft designed for operations including search and rescue, and coastal surveillance.

However, between 2013 and 2017 the reported value of acquisitions that were started within that time period was approximately USD18.5 billion. During 2017–22 the reported value, using the same timing metric, fell by 86% to USD2.6 billion.

In the initial period, most of this Chinese investment was in foreign companies operating in technology products and services including semiconductors and software. Semiconductors, in particular, were clearly a focal point for Chinese acquisitions during 2013–17, with 13 foreign firms acquired, mainly in the US.

However, during 2017–22 the number of acquisitions that reported the value of the transaction fell to less than half the total number of deals. Most of these deals were similar in technology and software sectors, but, of note, included just one foreign company involved in the production of semiconductors: an Israeli firm named Camtek.